This is a description of Priu, a fictional company which is a central actor in the equally fictional Great Retrofit world created as an output of the Science Fiction Economics Residency 2024.

![]() Back to the Great Retrofit world’s landing page

Back to the Great Retrofit world’s landing page

Priu is a construction and real estate corporation based in Messina.

Legal structure

Priu is a Type B social cooperative. According to Italian law, social cooperatives are cooperative firms that pursue the general community interest in promoting human concerns and in the social integration of citizens by means of the carrying-out activities, including agricultural, industrial, business or services, and having as their purpose the gainful employment of the disadvantaged (who must account for at least 30% of staff).

Name

Priu (also spelled prju) is a word used in many SIcilian dialects. It means “joy, harmony, satisfaction”. It comes from the reflexive verb priarse, “to rejoice”.

History

Foundation and early days

Priu was founded in February 2027. Priu’s initial business was connected with the ongoing effort to rejuvenate the shantytown built as a temporary housing solution after the earthquake of 1908 and in which, as late as the 2010s, 2,000 families still lived. This effort, led by the Messina Community Foundation, was committed to give the inhabitants of the shantytown a range of possibilities to choose from rather than a single-point solution. Some of these solutions required the renovation of homes purchased on the market; Priu was founded to carry out this renovation work while providing good-quality employment and an opportunity for reskilling to shantytown dwellers. Of the initial founding members, all but three were informal construction workers from the shantytown; two were construction workers who lived in other parts of Messina; one was a construction engineer.

Priu’s idealistic vision and its embeddedness in Messina’s social economy cluster made it a natural candidate for working on building and remodelling projects connected to this plan. Its first projects were relatively small, but they were already led accordingly to the Quintuple Bottom Line principles upheld by the Foundation. That allowed Priu to acquire experience in green building, participatory processes, including sometimes difficult dialogue with the marginalized communities involved in the shantytown reclamation plan, knowledge sharing and aesthetics.

U Scogghiu project

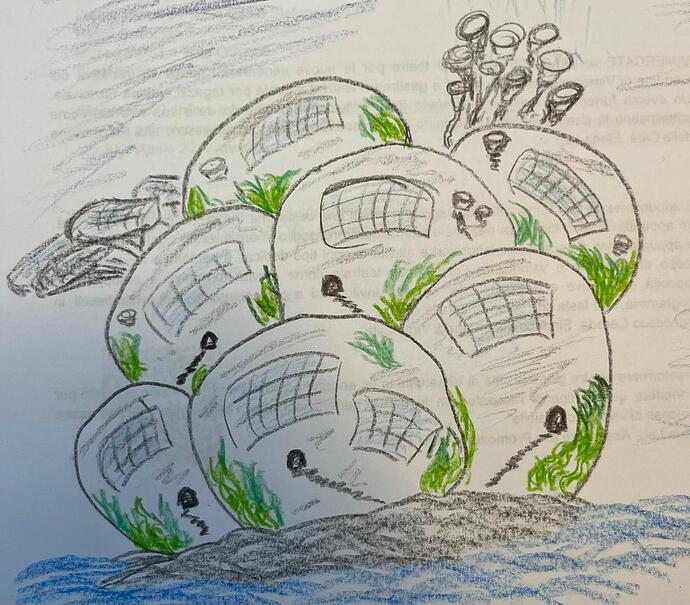

One of the housing solutions offered to shantytown dwellers consisted in joining a community, organized as a housing cooperative, that would jointly own and run a large – but, at the time, dilapidated – building in town. The Foundation wanted to experiment with cohousing, since it believed that tighter cooperation between people living in the same space would lead to high resource efficiency and a fulfilling life. There are economies of scale to living together: neighbors could work together to manage efficiently their energy generation and consumption (by forming renewable energy communities) their water management (by collecting rainwater and re-using gray waters), their mobility (by joint ownership of one or two electric vehicles) and even grow part of their own food in the building’s large garden. Though not everyone was interested in such a project, a group of 24 families agreed to join. This move entailed a large, ambitious, participatory building renovation project. Helped by the Foundation, Priu contracted or hired highly skilled professionals to provide solution to heat- and sound insulation, design and install solar panel arrays, rain– and graywater captation, filtration and reuse systems. The technical and social complexity of the project, combined with the emphasis on beauty and harmony inherited from the Foundation, led Priu to deliver a building with a peculiar aesthetic character, the first well-known example of the style that came to be known as Mediterranean solarpunk. Its dwellers called it U Scogghiu. Scogghiu, related to the Italian scoglio, is a Sicilian word that denotes both a marine rock and, metaphorically, an obstacle to navigation. Didier Mbaye, an U Scogghiu resident who would later become Priu’s Chairman of the Board, quipped that the building wanted to be a shallow rock to the ships of greedy landlords, by giving people hope in a more humane way of living. U Scogghiu attracted interest in the architecture world, and featured on the cover of Domus magazine in 2031.

U Scogghiu is incorporated as a limited liability housing cooperative (Società Cooperativa a Responsabilità Limitata), with all adult residents as shareholders. The cooperative acts as the economic and financial interface for the building and its inhabitants: it collects rent from the residents, manages and maintains the building, is a member of the district’s renewable energy community, and sells some services, like cultural events held in the buildings common spaces, food produce from its urban farm, and support and training services to groups who also want to start their own cohousing. Fondazione Comunità Messina’s former secretary general Giacomo Pinaffo, who already lived in a cohousing of his own in Padova, was appointed as a lifetime honorary member of the board without executive responsibilities.

Implementation of the Great Retrofit moonshot

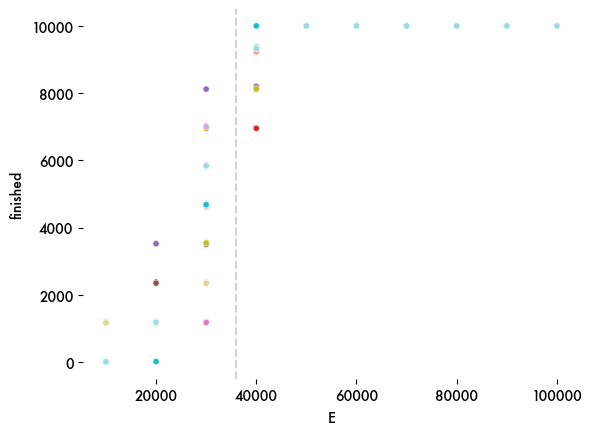

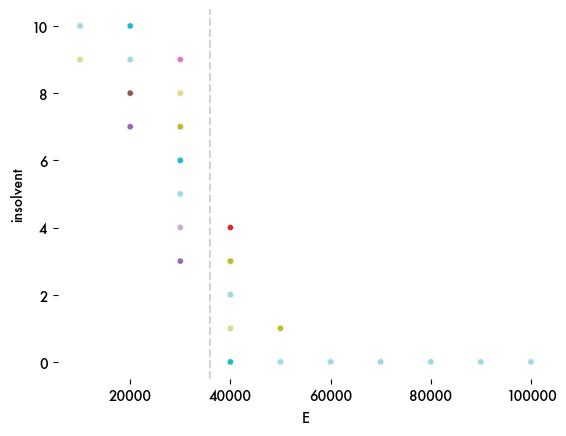

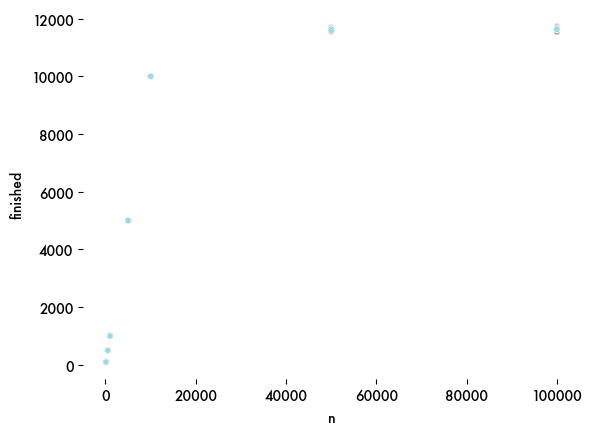

In 2034 the Messina City Hall, advised and supported by the Foundation, launched a “local moonshot”: retrofitting 60,000 housing units (60% of the city’s housing stocks) in ten years. The new policy was inspired by the ideas of Italian-American-British economist Mariana Mazzucato’s observation that setting ambitious, time-limited and verifiable goals, which she calls “missions”, stimulates innovation in directions consistent with the policy maker’s goals. Mission objectives are often called “moonshots” in tribute to the objective of the United States of America’s Apollo Program in the 1960s. With the housing stock retrofit moonshot, Messina’s became a mission economy focused on a green and social transformation.

The substantial new investments mobilized for the moonshot created a large market opportunity. At the same time, the new policy disposed that retrofitting operations must incorporate participatory elements, something most construction companies had little experience in. Priu, with its strong social element, experience in participatory processes, and the competences and prestige acquired through the U Scogghiu project, was asked to scale up to help deliver the moonshot in time.

Supported by the Foundation, Priu’s board accepted the challenge. It grew rapidly, hiring preferentially shantytown dwellers and themselves construction workers, most in informal or semiformal employment. Priu’s founders, who shared that same background, were able to reach out to many shantytown dwellers and convince them to join the Priu cooperative and embrace its way of working. It introduced power-sharing arrangements such as a decentralized management architecture based on sociocracy. The board itself expanded in numbers and grew in role, with several former shantytown members now finding itself not only in board seats, but wielding executive responsibilities. Mbaye, a Senegalese who had come to Sicily as a refugee when still a child, was appointed as chairman. He turned out to be exceptionally effective at representing the ethos and style of the company, and, in a broader sense, became a sort of figurehead of the Great Retrofit mooonshot.

Priu decided to prioritize retrofitting the largest condominiums in Messina first. This move made technical sense, because the largest building had the largest carbon footprint and the lowest retrofitting costs per unit. They also tended to be where the less affluent Messinese lived. This had the curious effect that, as the deadline for achieving the retrofit moonshot in 2044 approached, Messina became a place where the relatively poor lived in more efficient, modern, and often aesthetically attractive buildings than middle-class segments of the population. Additionally, the Foundation, Priu itself and other actors in Messina’s social economy cluster ended up acquiring several buildings that were also retrofitted by Priu. Their inhabitants were not evicted, as that would have clashed with Priu’s mission and statutes, but allowed to stay at an affordable rent, in what amounted to a de facto social housing program. Many of them chose to turn themselves into housing cooperatives, following the example of U Scogghiu and actively supported by the U Scogghiu cooperative. The combination of these two effects led to a noticeable improvement in the quality of life in the city, especially for low-income residents. Some commentators talked of “Messina model”, but most people used the more informal and catchy language of “Great Retrofit”.

Business model and source of competitiveness

Priu’s first business plan was completed in 2026. The business model described is straightforward: offer home remodelling services, with a focus on resource efficiency and preparedness for a world threatened by climate change. The business plan stated that the company had an opportunity to carve for itself a share of the Messina construction market leveraging the skills and ingenuity many construction workers in informal or semi-formal employment.

“Based on our experience, Messina’s underemployed construction workers may lack formal education, but have substantial technical and practical skills, and are hungry for opportunities for better employment and a better life. They could become much more productive and therefore prosperous by forming a modern, well-capitalized organization, consistently to the “stocks over flows” principle upheld by physicist and economist Gaetano Giunta.” – Priu scrl, Business plan 2027-2032

The business plan asserted that the Italian construction and building remodeling industry was, with exceptions, not fit to serve a green and social economy as Messina wanted to be; Priu’s founders believed they could outperform most competitors. The company’s statute committed to adopting a quintuple bottom line approach and power-sharing organizational arrangements, and to using short-term debt very sparingly. The Foundation leveraged patient finance from the ethical finance and cooperative sectors to allow the new company to make the first investments in staff training and equipment.