Super interesting!

Wow, @Hector: that was a hell of a comment. Way to go, and welcome to Edgeryders!

Many of us deeply sympathise with the DIY approach, and almost everybody in Edgeryders struggles with the “tyranny of the mortgage”: I myself have chosen “co-living”, a large space shared by three adult couples. I often wonder how societal dynamics would change if Europe was more like Thailand, where I’m guessing a simple thatched home with bamboo structures must cost like a large car. Thailand is favoured by a climate that makes insulation a very low priority, but even in Europe we have technologies for living in alternative to the house or condo, from containers (look at this fantastic thread about how to live in them!) to house-sized 3D printers. Where we get stuck is building regulation: anything cheap or provisional is forbidden.

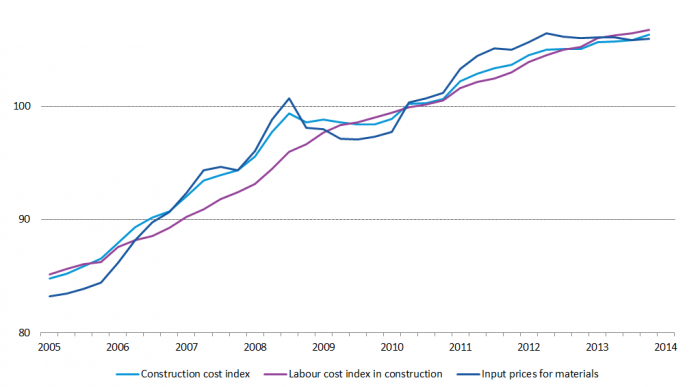

The construction industry is a very important source of jobs (over 13 million employed in Europe – source), so the last thing the regulators want is N “uberization of construction”. As a result, it seems, real estate developers lobby for ever more stringent regulation that are impossible to comply with for a group of friends, however skilled and resourceful like @trythis or @Matthias, who want to try and build their own home. As a result, the price of construction has doubled in ten years:

We are not going back to mud and mortar any time soon. Which is sad, because I think you are dead right.