Many people around the world are trying to bring about change. If you are hanging out in Edgeryders, you are likely one of them. What we are trying to change, exactly, depends on individual levels of hybris. It can be personal habits, a city, a business, or the whole world. But, at any level, we have two decisions to make:

- What to start. There are many things we could attempt, but most of the interesting ones are hard. Most will fail. And our resources are scarce: we only get one or two tries every few years, at best. Which one do we pick?

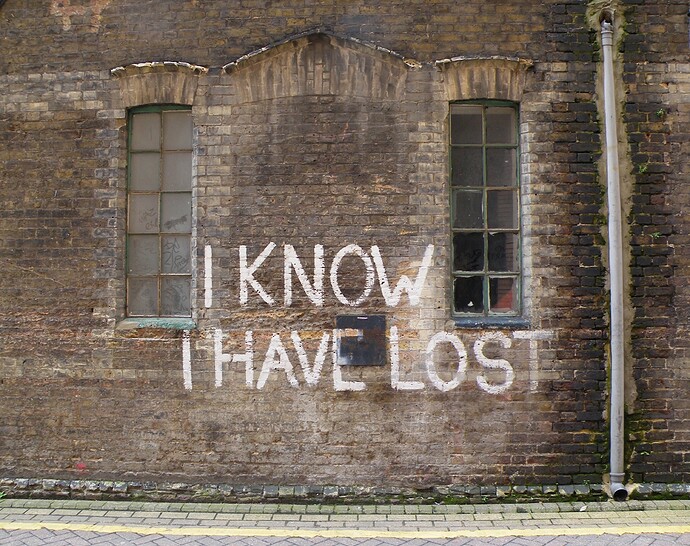

- When to stop. Picture this: you have been trying to make a certain change for a couple of years. You have not completely failed: you are still standing, and making some progress. But it is not clear your succeeding, either. Your movement is gaining activists, but you are not making a dent in the issue you care about yet. Your company is viable, but it cannot afford to pay market rate salaries yet. Are you winning or losing? Should you keep at it or cut your losses and quit?

I recently spent some time going through the work of Eliezer Yudkowsky. He has a knack for applying tools from epistemology to real-life problems. He has some advice to offer, especially on what to start.

His argument is this: many things, in the world, are broken. But this does not mean they are also exploitable. An exploitable situation is one that is broken and you can gain immediate advantages by fixing it and no one is already trying to fix it. At least, not in the same way as you.

Financial markets are not exploitable. If you can figure out a way to “beat the market”, others will imitate you, because this will make them money. Soon everyone will be back on a more or less equal footing. In econ-speak, markets are efficient: if there is any free energy lying around, it is easy for anyone to eat it. So, there is never any free energy lying around. Yes, you economists out there, markets are not always efficient. But this is a story for another day.

Policy errors are not exploitable, for a different reason. Imagine you figure out that the Bank of Japan is making a mistake on its monetary policy. Then what? You cannot make money by delivering a better monetary policy to the people of Japan. The Bank is a monopolist. There is free energy, but you are not allowed to eat it.

So what is exploitable? Yudkoswky’s example is this: he was able to treat his wife Seasonal Affective Disorder. This is a common condition, and a treatment exists, but did not work in this case. So, Yudkowsky tried a tweak of the method that did not exist in the medical literature, and that turned out to work. He beat the whole medical profession to it. How did he pick this one fight? Well, he cares about his wife, of course. But besides that?

Yudkowsky thinks tractable problems are those with

a system with enough moving parts that at least two parts are simultaneously broken, meaning that single actors cannot defy the system.

Two of the broken parts in the SAD treatment are academia and academic grantmakers. Academics need to publish in the best journals, or perish. Grantmakers need to see their grants turn into publications in the best journals. Research on the effect of tweaks of existing treatments, reasons Yudkowsky, does not make the best journals. So, it is conceivable that it does not get funded: it does not happen at all. At this point he had a hypothesis: “This tweak on SAD treatment has not been researched.”

Preliminary testing of the hypothesis was easy. A session of Googling, plus skimming a second-hand book on SAD reported nothing. At this point, Yudkowsky decided that trying his tweak was worth a shot. He spent a few hundred dollars on materials (as certain type of light bulbs), and ran a test.

In the toy model of medical research above, neither academics not grantmakers have any incentive to deviate from what they are doing. Mathematicians say the model is in Nash equilibrium. Yudkowsky calls these equilibria inadequate.

The situation is: only inadequate equilibria are exploitable. But only a few of them are: inadequacy is everywhere, but most of it is unexploitable. The money quote is this:

you do not generate a good startup idea by taking some random activity, and then talking yourself into the idea that you can do better than existing companies. Even when the current way of doing things seems bad, and even when you do know a better way, 99 times out of 100 you will not be able to make money by knowing better. If somebody else makes money on a solution to that particular problem, they’ll do it using rare resources or skills that you don’t have. Including the skill of being super-charismatic and getting tons of venture capital to do it.

The solution is to “scan and keep scanning” for “winnable battles”. Warning: they are rare, not only in business but in any competitive environment. And almost always, they don’t involve fixing the systems, but improving it a bit.

Following this advice implies navigating a course between realism and ambition. You should not be modest and defer: sometimes you can do better than anyone else. But you should be humble: most of the times, you cannot.

The same attitude seems useful for deciding when to quit. Most of the times, things that do not succeed fast, will never take off. But sometimes they will. You need to “scan and keep scanning”, and decide when it is time to call it quits.

I’m curious: how do you choose your own battles? And how do you decide when to abandon the battlefield?

(Me, I’m going to look further into epistemology)

Photo credit: Cathy Davey on Flickr.com