A big part of my family is Ethiopian. This is also the main reason I packed my bags and headed off to Addis Ababa

… to participate in my beautiful cousins’ weddings.

My cousin made clear I was expected to show up in a Habesha Kemis. So on arrival I headed off to Shiro Meda to find a tailor.

I liked it so much I ended up getting a second one made.

The wedding itself was a ball. With our family being spread across the globe it is rare for so many of us to be in one place at the same time. I really appreciated being able to spend time together in celebration of the most important element of a happy life… love.

On the ride to venue where we would dance and try to keep the groom from picking up the bride (yes, literally- tradition), we came into the topic of religion.

I was asked about my religious beliefs which struck me as quite an odd question. .

… Until I found myself in the middle of a massive Timket (Epiphany) procession in a different part of the country a week later.

The same thing happened on numerous occasions in different parts of the country.

Religion is a big deal in Ethiopia. So is peace.

So Ethiopia is home to oh about 200 ethnic groups and around 80 languages. However diverse I knew the country was, in my mind always was associated with Christianity and Judaism… a long history that began over 2000 years ago. The Hebrew influence and identity is pretty clear when you wander around Gondar and Lalibela, especially if you dig into historical information about different dynasties that ruled and shaped Ethiopia throughout the centuries.

So I was surprised to learn just how large a proportion of the population the Muslim minority is. Almost 40 percent, if I’m not mistaken. And that the one Jewish person in the Bet-Israel village is the guy running the museum frequented by tourists on pilgrimages. Where is everyone?! Oh yeah. Pretty much everyone was evacuated to Israel after the massive drought in the 80s.

I feel a link to this diaspora, all diaspora really. There is something those of us born with feet in many worlds discover sooner or later. That we are not one or the other, but something else… ours are third, remix, cultures. Religion is one of those sensitive areas we have to develop mechanisms for navigating.

Within my family there are ties to several mega-cities of Africa and Asia where more than half of the world’s 1.3 billion Muslims, and around sixty percent of the world’s 2 billion Christians, live. I was born and have lived in different parts of a Western liberal Europe not sure how to deal with growing tensions between different social groups.

Here and there, what we think of as religious and or ethnic conflicts are often intimately tied to underlying conflicts over resources like land or water.

Rwanda is one of the most densely populated countries in Africa and the pressure on land has often been put forward as an important factor in the 1994 genocide. I cannot remember where I heard that in the case of Rwanda there were more intra-ethnic murders than between different ethnic groups… the genocide was partially fueled by the need to free up resources. If memory serves me, they had a system ( currently being reformed) in which all land would be passed on to the first son. Which left a class of landless, disenfranchised young men with no hope of accessing a brighter economic future unless some of that land could be freed up…

Israel and Palestine is another example. At the source of this conflict, according to Bo Rothstein, lies mixing of religious rhetoric with what is essentially a struggle over assets. He claims that you would create the foundation for lasting peace by focusing on resolving the land/economic disputes with compromises for everyone (Swedish article): http://www.svd.se/…/markavtal-kan-stoppa-valdet_3777014

Other examples of legacy injustice include (thanks @Jaycousins ):

Egypt - land is divided amongst all children so within a couple of generations everyone has a tiny patch they can’t profit from - the result is illegally constructed tower blocks on most of the rare and fertile land in Egypt and a lot of in-family tensions.

Likewise In England or any other Western Country, the peasantry had their inheritance stolen out from under them long before the lords and merchants started robbing foreign soil.

… There is much to be learned from Ethiopian history about the importance of tackling inequalities in distribution of property and use rights for building lasting peace. Especially in societies where formal property laws and customary property rights arrangements exist in parallel. I believe some of those lessons are also relevant in societies where land rights are secure but ownership of property is highly concentrated.

Fixing legacy injustice: Reforming dysfunctional property laws and peace between ethnic groups

Justice is a prerequisite for peace. While the murderous fascist regime known as the Derg got a lot of things wrong, they did push through land right reforms.

Prior to the civil war against the old feudal order (Haile Selassie, also known as Ras Tefari), the Muslim population was excluded from being able to access land as they were passed along hereditary lines. So your family had to own land in order for you to have hope of owning land. This was the Ristegna system.

Then there was the Gultegna, the nobility, which were granted the right to a fat chunk of the surplus from the land tended by farmers. Basically a rentier class that contributed little or nothing to the development of the country and life of their fellow Ethiopians.

Both were upended by the revolution and land redistributed and finally nationalised. Why?

One of the persistent calls for social justice in the revolution, also during the Derg period, was “land to the tiller”. All the different interest groups got behind this reform as a fundamental requirement. The military dictators could not back out on this demand as they would loose legitimacy amongst the soldiers, many of whom hailed from the southern parts of the country where the problems of unfair distribution of land was particularly strong for historical reasons.

There are still problems, and new ones. Ethiopia is also undeniably doing a lot better than many of the other countries in the region- my impression was that there is a fundamental belief that things are improving, also for those at the wrong end of the power spectrum. Clearly the picture painted depends on who you ask but I could see for myself that e.g. infrastructure is much better in many parts of the country than it used to be.

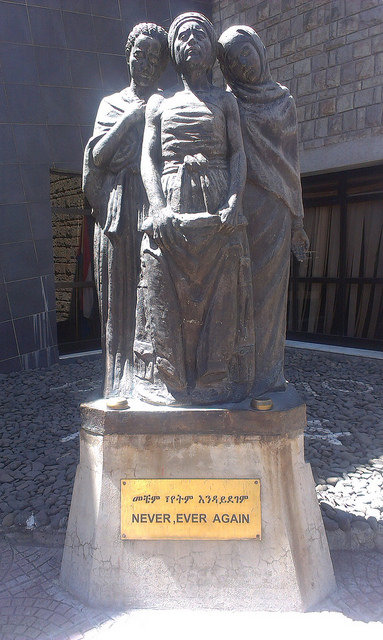

Most of all people are very aware of how fragile and important peace is. The story of a popular revolution co-opted by a military regime that then did its best to murder an entire generation is still fresh in the collective memory. I am reminded of this every time I hear any talk of revolution: the move towards a western style liberal democracy is not one that Ethiopians I spoke to value highly. Rather, it is economic rights and development that seem to be at the heart of their concerns.

If we are to achieve peace at home, we need to think about how we tackle legacy injustices against people in different parts of a globalised world. The central pillar is property law and ownership. As Ethiopians learned, it makes sense to start there and not let up till an acceptable solution is reached.

There will be losers. However if they are taking up so much space that it threatens the ability of others to survive. Well, they… all of us, may end up losing a lot more than excess capacity.