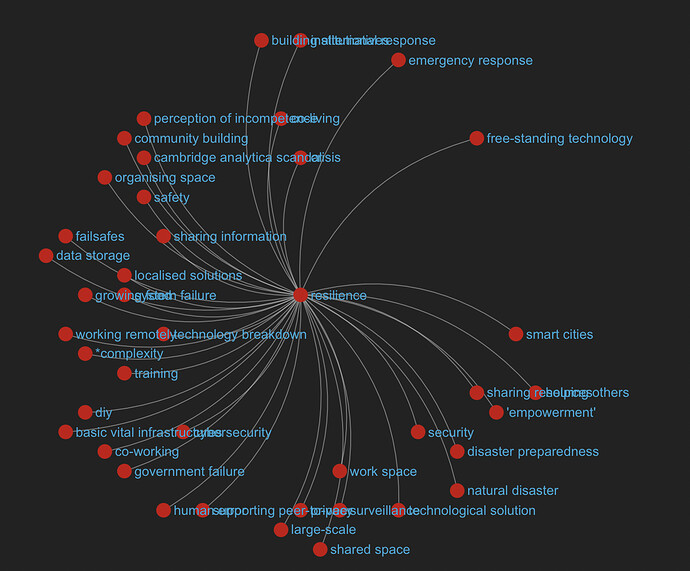

While my last two reports (here and here) unpacked topics around the “future of work”, this month’s report is devoted to the second of three broad thematic areas I laid out in my first report: Resilience, Welfare and Sustainability. Topics in this area, cluster around questions of how technology variously interacts with our health and welfare, our vital infrastructures, the climate and our natural and built environments. Ultimately, these debates push us to consider – in a very holistic sense – how technology can allow us to thrive.

As I have in all past reports, let me begin this one with a consideration of futures. In past reports I have discussed how debates around the future often fall along a spectrum from utopian to dystopian.

Visions of dystopian futures often include scenes of natural disaster, the spread of disease, the total collapse of infrastructures and the breakdown social networks. Utopian futures, meanwhile, envision new cosmopolitan modernities; the rise of a new political dawn and resilient communities built on the promise of digital technologies. There are few topic areas on platform where the binary between utopian and dystopian is as stark as it is when it comes to considering the complex ways in which technologies interact with and impact our health, welfare and environment: how might the development of digital technologies contribute to an increasingly dystopian future? And, how can we harness the potential of digital tools to improve our existing systems and pave the way towards a resilient and sustainable future?

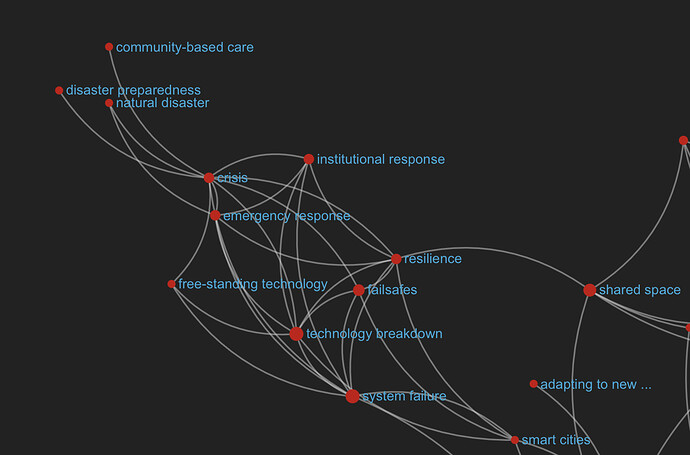

The pandemic has brought renewed urgency to assessing the stability and preparedness of the tools we have available to ensure public health and safety and to enable our communities to recover and remain resilient during disasters. What do we need from tech in times of crisis?

The Temporalities of Crisis

As the anthropologist, Rebecca Bryant (2016) argues, times of crisis – or what we perceive to be moments of crisis – can make our present feel uncanny. That is to say, they are experienced as “anxiously visceral” moments, “caught between past and future” (Bryant 2016: 20). While Bryant and others concede that the very notion of crisis is neither neatly definable, nor equally perceived (in fact, one could argue that the term has been used so broadly in recent discourses that it is devoid of meaning), a consensus does remain that examining individual and collective notions of crisis (as they are used and responded to locally), gives us important insight into the ways in which we utilise the past and make sense of our futures. To Bryant, moments of crisis are critical thresholds: moments, both liminal and decisive, which exist outside of ordinary time; hovering between past and future and yet pivotal sites for new forms of action and decision-making. Another (though similar) way to think about crisis, as anthropologist Janet Roitman posits, is as a “transcendental placeholder because it is a means for signifying contingency” (Roitman 2014: loc 320). In Roitman’s view, an event is read as a crisis because it shows that the world could be otherwise; a departure from the “norm”, which shows the various other forms the present (and future) can take. Equally, moments of crisis, so Roitman, can clarify new directions forward: to identify otherwise unpredictable possibilities.

For now, let’s return to Bryant: if moments of crisis – perhaps the very moment we are currently experiencing – are critical thresholds, how then can our current technologies be harnessed as decisive tools for building our futures?

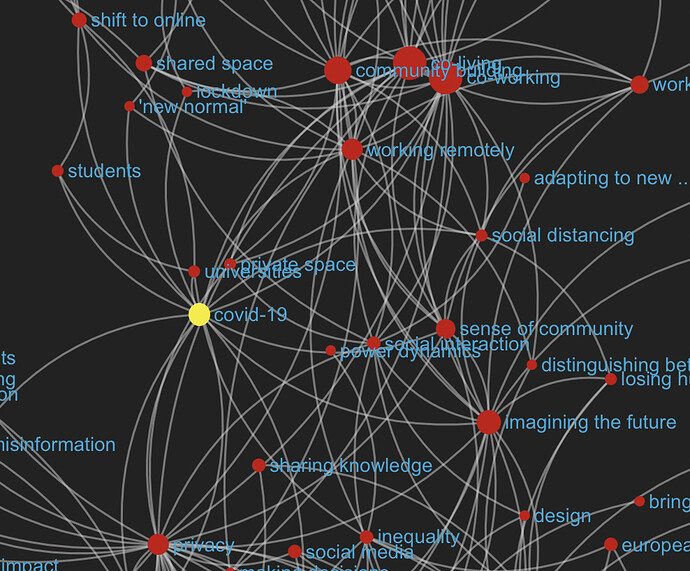

In April 2020, as the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic was sweeping through most of Europe, the Edgeryders community sat down for a virtual conference. We talked to experts in the European legal community, medical and public health, digital tech, privacy and human rights, public policy and media to discuss the ways in which digital tools were being used and developed to combat the pandemic. As @Alberto, one of our community managers asked, “people worry, but no one is sure what an appropriate diagnosis and response to the situation would be. Is the situation ‘problematic’ or ‘dystopian’? Can we do anything about it, besides worrying?” (@Alberto 2020).

Bryant argues that what makes the present uncannily present in times of crisis is our sudden inability to anticipate the future. Put another way, the present becomes uncanny because the links between past, present and future that ordinarily allow us to anticipate, become severed (2016: 21). In this sense, the worry that Alberto’s question pinpoints, also signifies the urgency to repair those ties; to be able to anticipate the future by identifying familiar anchoring points. However, during our call, there was a second kind of worry, that of the possibly dangerous and, in some cases, untested effects of using digital technologies to combat the pandemic. Alberto and others warned against snap decisions: against a kind of solutionism that is more focussed on quickly fixing problems as they occur without considering their broader implications and long-term effects.

Many agreed that the rush to deploy contact tracking apps, immunity passports and similar technologies forced an unnecessary trade-off in which civil liberties may be sacrificed in the interest of fighting the virus. At the time, experts warned of three major risks: a) in the absence of a clear privacy-friendly solution for the development of these technologies, it would be unclear where data would be sourced from (and by whom) and how it would be regulated, b) there was an unequal distribution of risk as it could lead to the disproportionate targeting of vulnerable communities, and c) there was an absence of the counterfactual, meaning that, at that point, we didn’t know enough about the effectiveness of allowing (digitally mediated) ‘normal life’ to resume and it was therefore risky to develop strategies without clear, counterfactual knowledge to work with. This brings up two important points: the first is that we do not seem to have created a way to learn from past pandemics and to use this knowledge to address present and future ones. The second, though related point is that – though a new global pandemic had been predicted for several decades – we lack a sense of collective urgency through which to prepare for or anticipate crises like the covid-19 pandemic.

The uncanny present, so Bryant, seems to foretell the future in a way that repeats or returns to the past: the past, hereby, is not any random moment of the already, but a traumatic past retained as a visceral experience. As Bryant ultimately argues, in order to be able to anticipate, we not only need to use “signs, symbols, and stories from the past” but rather “the bodily and visceral responses” that constitute them.

Is there something so unimaginable, so outside of the “ordinary” about global health crises like the covid-19 pandemic that make them so difficult to anticipate?

As I have flagged in other reports, one ongoing limitation seems to be that when governments and policy-makers talk about the future, they often mean the near future. Barbara Adam and Jane Guyer have described the short-sightedness of many modern democracies, who often make short-term decisions (relevant in there here-and-now) that while having consequences for the long-term future, fail to anticipate or address their enduring implications. Despite calls for policies to take long-term perspectives, not enough is being done to expand our view of the future and the role of digital technologies within it – particularly as we strive to build more resilient communities that can more easily respond to and withstand crises. In a similar vein, participants in last year’s event point to both immediate and long-term implications of using digital technologies to combat the pandemic: on the one hand, they argued that policy makers overestimate the effectiveness of tech-based surveillance tools to counter the spread of the virus, meaning their was little attention paid to short-term ramifications of deploying further surveillance technologies outside of tracking and tracing.

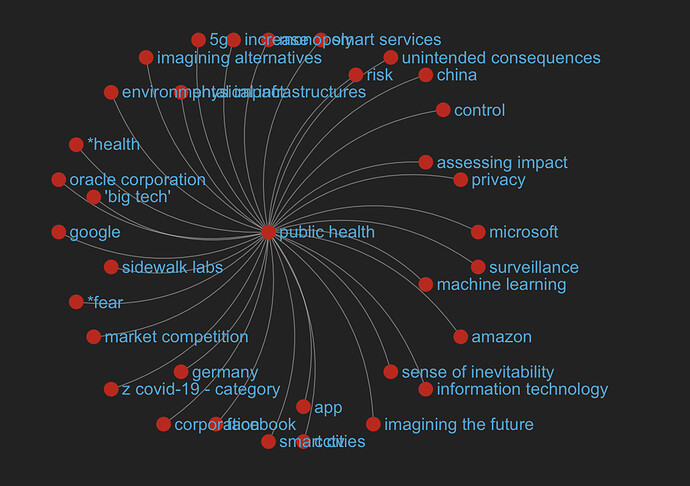

In this way, a question is: what kinds of short- and long-term risks and potential harms do we unleash when we make snap decisions about deploying technologies in times of crisis? What kind of failsafes do we have in place to counter these potential harms, should they occur? While some members pointed to the GDPR and the European Convention on Human rights, scepticism prevailed over our ability to safely deploy such technologies – even in exceptional circumstances. There was also concern that surveillance tools were now vulnerable to exploitation by companies that saw the pandemic as a business opportunity. This concern certainly came true over the course of the pandemic – or at least in part: one of the biggest financial profiteers of the covid-19 pandemic were arguably Big Tech companies. @katjab summarised the problem well: “Where most sectors of the economy have seen demand collapse, many large tech companies are reporting record profits 2, and have been able to use this momentum to further consolidate market share. With more of us reliant on technology for our daily lives than ever before, we have become more willing to turn a blind eye to the excesses and ethical shortcomings of these companies and their business models. The so-called “end of the techlash” would no doubt be seen as a welcome break after years of negative headlines and mounting public pressure”, and goes on to ask, “but will it turn out to be a temporary respite for the internet giants, or are we witnessing a more permanent concentration of power over yet more aspects of our society and economy?” (@katjab 2020).

The pandemic not only put our public health and medical institutions under unprecedented strain, but global lockdowns also forced many of us – those of us who have the resources to – to confine most of our work and everyday needs to our homes. This meant that our work and education relied centrally on the capacity of digital tools to enable us to pursue our livelihoods. Acquiring everyday necessities, from clothing to groceries also largely shifted online. As we have seen, this has greatly enriched the tech giants who, even before the pandemic, dominated much of the industry. However now, they enjoyed even less ethical scrutiny. As @katjab so lucidly puts it, looking toward the future the fear is that Big Tech will not only continue to dominate, but that its dominance may take on new and more all-encompassing forms. This certainly brings visions of a looming future dystopia screaming to the fore, where our private data, security and identities are in the hands of a small number of tech giants whose motives and business practices remain opaque and under-regulated. But even outside of these dystopian visions, it does raise an urgent question about how the rapidly increasing monopoly of Big Tech may intervene with efforts to build a more human-centric, safe and transparent future of the internet. What can we learn from this present moment of crisis – which is in many ways being exploited by tech giants – as we continue to pursue a more just future for human-tech relationships? And, what can the present teach us about how to prepare for the future?

Let’s return to the community call and our conversation around track and trace apps: many community members argued that while contact tracing apps are ineffective against Covid-19 (see the case of the German model), they may be potential tools to combat future pandemics. While most in the group agreed that tracing apps could, in principle, be enormously effective tools, they agreed that in their current form tracking and tracing apps simply faced too many data governance issues, and, relatedly, could not assuage public mistrust of government-sanctioned technologies. This partially also affects the apps’ low levels of uptake across Europe, which make them even less effective. Members on the call cautioned against the “rush to deploy” tracing apps, which had been emerging in weeks past, for the current pandemic, arguing instead to take this opportunity to start building a trove of resources to prepare for future crises: to learn from the immediate past (i.e. the failure of recently developed technologies) to prepare for future scenarios.

Returning to Bryant once more, we can see that the present offers us the opportunity to gather “the past and projecting it into the unknown future” (2016: 24). That is to say, in times of crisis we can draw on various pasts to think about possible futures (the not-yet).

Importantly, this reserve of resources members envisioned also includes pooling together knowledge from a range of fields: from medical researchers and practitioners, policy-makers, local governments and tech experts. In this way, the community agreed, we could start to better anticipate what we need to do in times of crisis and how technology can intervene: from supporting doctors and community organisers by streamlining remote diagnosis and digital prescriptions, to optimising communication technologies and the dissemination of vital information, to assisting in the production of medical equipment. Crucially, this also means studying the history of pandemics and health technologies and using this knowledge to build better tools to withstand future crises. As one participant summarised: “the dialog between the technologically possible and the politically acceptable needs to be had. Immediately it will be done by the elected politicians, that is what they are there for. Then, we should be moving to broader participation. We should be building technology for participation, as much as we should be building technology for tracing”. Anticipating future crises, means determining what we need our tools to allow us to do in the long-term, and to design them accordingly.

This brings me to my next point of inquiry: Public Health and Welfare.

Health and Welfare

Themes of resilience and sustainability are central to understanding the relationship between digital technology and public health. Access to healthcare, for example, is an important domain in which technology plays a key role. On the one hand, the internet and other digital technologies can make access to crucial healthcare information more widely accessible. It can enable to us to make informed decisions about providers and it can help us access our own health data. During the pandemic, digital technologies allowed us research and share information about the virus, to track its spread and locate testing and vaccination sites. In this way digital technologies can offer quite a lot of agency to individuals and communities and foster the development of support networks, and build new lines of communication and aid. They also allowed us to maintain contact to our friends and family, seek online counselling, join courses and exercise groups, and access a broad range of entertainment options in film and media. All of this greatly contributed to our mental health.

However, there is a flip-side to our increasing reliance on digital technologies, some of which I have discussed above. Community members have also pointed out that our use of digital technologies can heighten anxiety, our sense of isolation and desires for human contact. There is a concern about how our data (health, biometric and location) is being stored and used, bringing renewed urgency to questions of regulation and transparency, as well as the risk of exacerbating disparities in healthcare access. Community discussions about the relationship between tech and health have shown that digital tools can often become double-edge swords.

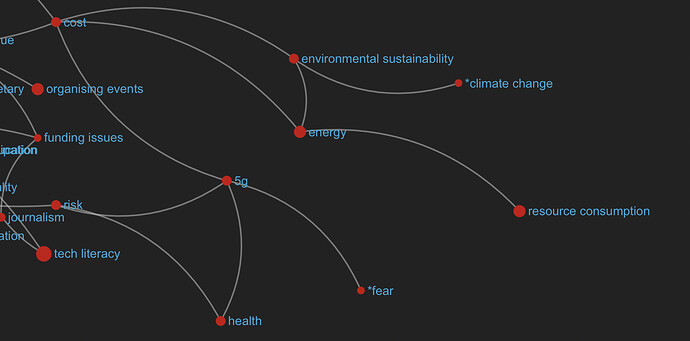

Let’s consider the so-called “5G scare”. On the one hand, there is a push for our cellular devices to work faster and run smoother – this requires increasing band and radio wave frequencies, which in turn require a greater distribution of cellular towers (and 5g antennas). There are obvious incentives for consumers and companies alike, however, as one community member warned: “[governments/countries] spent billions to develop and install technology and they spent 0 Euros to actually study the effects on health…that’s insane. When I manufacture a product in China and import it to the EU everything is checked for safety/health concerns, even [the] type of plastic/paint etc and nobody is checking this…unbelievable” (@jasen_lakic 2019). While concern over 5G’s possibly detrimental health effects was shared by some members of the NGI community, the bigger consensus lay in holding businesses and governments accountable: shifting focus to greater long-term research, to intervening in the spread of mis/dis-information, to ensuring public health safety in the implementation of new technologies. They have also reminded us to remain vigilant in our resolve to build human-centred technologies. As @mattias explains, building human-centric alternatives to our current models means addressing the question, “if humans are to use the internet, what are the absolute necessary need[s] that humanity and natural resources can handle?” (2019). This means considering how public health and welfare interact with (or rather, rely on) our environment and infrastructures, as well as to assess what exactly we need from digital technologies to allow these co-constitutive domains to thrive.

Climate and Environment(s): how can the internet protect the climate?

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, discourses of crisis often circle around themes of climate and environment: climate crisis, natural disaster and environmental emergency are abundant terms in contemporary debates, even on the NGI platform: “The apocalypse has a new date: 2048. That’s when the world’s oceans will be empty of fish, predicts an international team of ecologists and economists. The cause: the disappearance of species due to overfishing, pollution, habitat loss, and climate change” (@johncoate 2019).

The threat of ongoing climate disasters has lead many on platform to bring in a more nuanced focus on (a) how the tech world may be contributing to environmental harm and (b) how digital tech – and the tech community more broadly – can hem global warming and protect the climate through sustainable solutions.

Like many debates on-platform, talk around climate and environment begin with deep conceptual work: community members share a sense of responsibility to revisit, question and reframe the often taken-for-granted concepts and practices that we come to use when we speak about tech, digital tools and virtual life. What does it mean for technology to be ‘green’? Can tech be truly environmentally sustainable? Are we addressing climate change from all angles?

Community members have pointed out that the growth of the tech industry and tech products, more broadly, can significantly harm the environment, from un-recyclable devices and bi-products to their energy consumption. This includes the carbon footprint of online streaming and the green house gases generated by the energy needed to transmit streaming content, so-called data “bloating” and the exorbitant green house gas emissions generated by data centres. As @Johncoate points out, we are facing new forms of energy consumption and carbon emission that are eclipsing the effects of non-bio-degradable materials like plastic: “the amount of that plastic has gone way down (from 61 million kilograms in the 2000s to about 8 million kilograms as of 2016), but at the same time the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere that can be fairly attributed to the amount of power required to serve all that streaming is huge and dwarfs that amount of plastic” (2019). The rapid emergence of new and drastically more harmful tech bi-products, means we need to more effectively research, assess and weigh out the potential benefits of tech development against the immediate and long-term risks they pose for environmental health. However, as many on the platform have pointed out, “the problem is that we do not have a valid intuition for the carbon footprint of most modern activities or products. How could we work towards the development of such awareness and intuition?” (@mariaeuler). Again we find a tension between our drive to innovate and develop new technologies and our ability and willingness to predict and anticipate their potential harms. Recent conversations around crypto-currency mining and its potentially detrimental climate implications, make the call to assess and regulate tech-environment relationships even more urgent.

In response to the palpable environmental impacts of technology, several threads on platform have revolved around the notion of Deep Green Tech. While there is a lot of interesting discussion around this concept, it has yet to be clearly defined by the community. And perhaps that is part of the idea: Deep Green Tech is similar to Deep Tech in that it mainly describes startup companies based on substantial scientific research and innovations in tech engineering. However, Deep Green Tech, also seems to more broadly describe technology that is ecologically sustainable, innovative and based on scientific advancements. In this way, it appears to represent a larger idea or movement, capturing a sense of collective commitment to making our technological tools better for the environment. As @Johncoate, argued during a 2019 discussion on deep green tech, “given the situation we collectively find ourselves in, I think that definition[s] should be as inclusive as @pbihr suggests: materials, sources, processes, recyclability, shipping, packaging, energy use - all of the above and whatever else goes along with it”. Such an holistic approach to making tech ‘greener’ has pushed many community members to offer up their ideas for deep green tech solutions.

On the one hand this means building more robust tools through which to predict, measure and control climate change. As one member suggested, this could mean using digital tools to measure climate and greenhouse gases: “we will be able to better control our emissions if we know where they are happening and be able to make better predictions if we know what is happening in the climate today. We need to be able to transmit the data we collect around” (@eb4890). The same community member also urged that we harness the potential of digital technologies to track changes and control electricity consumption and thereby develop more efficient tools for predicting the climate and monitoring energy waste.

Another key area of inquiry was how we ensure and verify that our tech products really are ‘green’. Such considerations have centred around the use of “green trust marks”, which would allow us to asses the environmental sustainability of electronics and other tech products. As it seems now, the idea of green trust marks are still largely conceptual, and the question remains whether these trust marks aught to represent the minimum or ‘gold’ standards from which we measure the ecological costs of tech products (and bi-products). As @pbihr points out, the challenge in both setting up trust marks and ensuring that our products are ‘green’ lies in the complexity of the products themselves. That is to say: when we assess whether or not a product is green, we need to take into account far more than just its physical parts, or materiality (from the kind of chips it uses to the materials that product itself is made from). We also need to consider how and where the materials are sourced, to what degree the materials are repairable or recyclable (and how those processes work). We need to account for how the products are packaged and shipped, and we need to take a big picture view of the energy use involved in all of these aspects: from sourcing, production, shipping, consumption/use and disposal (or re-use). All this considered, it is clear that there is no neat nor easy way to ensure that a tech product is completely green. While there are no blanket trust marks to work with currently, one promising route for the immediate future seems to be creating better transparency around electronic products, as well as building searchable data bases that report on their environmental impact. This can help us monitor and measure them from a policy and design perspective, but also allow consumers themselves to make informed decisions about the products they use. Community members see a great deal of potential in tools like Good Electronics Network, MET (material, energy toxicity) Matrixes, EcoCost and in establishing different types of repairability scores.

As @pbihr goes on to emphasise, we need to use the present to start asking the kinds of central questions that will enable us to move forward sustainably and responsibly: “how can we mitigate the lack of transparency and still get to meaningful insights into how green a product is? What are best practices to make things more green? What are strategies to allow for this type of mark to evolve as things get more transparent over time?” Importantly, these kinds of questions link to broader discussions of community and responsibility. Community members are concerned with defining the responsibility of policy makers, governments and big tech to protect the climate (and thereby also calling out corporations, governments and individuals who are failing to do so). Ultimately, as @soenke stresses, this means creating and promoting an “holistic concept of openness”, which takes into account all factors that play into tech’s impact on the environment.

The Built Environment

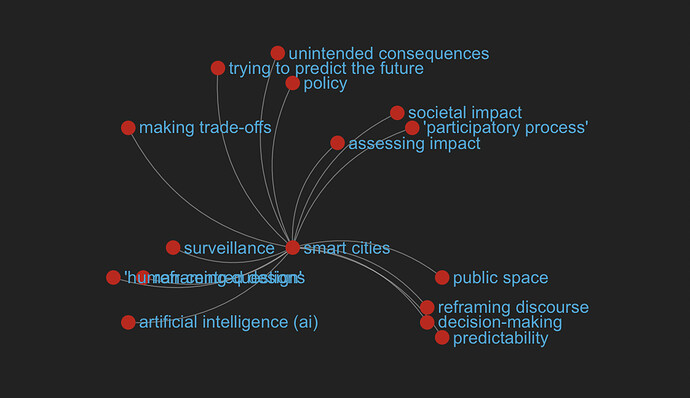

Smart cities and smart devices are often cited in debates around green and deep green tech. So, For now, let’s take a moment to consider our built environments and how these may allow us to protect our natural surroundings. On the NGI platform conversations entered around how we can build human-centred and sustainable cities and infrastructures. How can we design cities that are not only environmentally sustainable, but also resilient?

What does it mean for a city to be smart? And, do we really want our cities to be smart? Smart cities might broadly describe “the integration of several system-management cities, from energy grids to traffic, into one coherent whole” (@BasBoorsma; @gordonfeller). In short, smart cities manifest as digitally mediated urban design, or, as @Nadia puts it, as sites “where the digital and physical meet”.

As Bas Boorsma describes, a “Smart City”, where it is a “vision”, can be BOTH an organic iteration of innovation (by not just those 2 big companies, but by many others) AND it can be a societal shift stimulated by numerous simultaneous realities (climate crisis; economic inequality crisis; pandemic; etc.). Given the range of potentials and possibilities smart cities seem to bring with them, it is important, as @pbihr makes clear, that when we think about the future of our built environments, we first conside : What are better urban metrics in cities increasingly governed or shaped by algorithms? How can we put people first and make sure that their cities, their public spaces and agoras work for all of them and not just for the companies that sell some of the infrastructure? (2019). Returning to the points I highlighted about deploying new technologies in times of crisis (at the beginning of this post), it is also, vital to consider the immediate and long-term impacts of technologies in future utopian projects. Smart cities, in their most general sense, might envision urban landscapes in which human resilience is enabled through digital tools. However, as many community members have pointed out, their implementation is far from straight-forward. Nor are smart city designs unproblematic: concern exists over how smart cities may lead to further and harsher surveillance technologies, how the gathering, storing and usage of data will be governed (see eg plans for Alphabet Sidewalk Labs in Toronto, which have been discussed on platform), how the development of Smart Cities could further incentives exploitative business practices – especially among Big Tech – and the various (often unpredictable) ways in which algorithms will interact with our daily lives. We have substantial evidence that show that the use of algorithms is particularly dangerous, harmful and racist at the hands of law enforcement and within policing practices, more broadly (eg predictive policing). Enormous and urgent concern therefore exists around how the increased use of algorithmic systems within Smart Cities will further exacerbate bias, discrimination, injustice and inequality.

As @pbihr and others have urged, while smart city project continue to proliferate in our future imaginaries, we need to find ways to ensure that their design and implementation are human-centred and participatory, environmentally sustainable, properly regulated and transparently governed. @tomab (2019) took a similar view, arguing that while there is an air of inevitability around the development of smart cities, it doesn’t mean we need to be complacent. Instead we can steer their development by creating standards for their design that protect and enhance humanity (though, this is arguably very difficult), by educating the public about technologies and how they interact with the world, and by identifying the benefits of smart city designs and introducing them to more local and distributed communities. Some community members have proposed that smart city projects need to be aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, human rights, and the simplified TAPS framework (Transparency, Accountability, Participation, Security). What is more, all smart city projects should be built as carbon-neutral alternatives to our existing – highly pollutant– current urban spaces. There is thus a sense of opportunity and momentum behind the notions of smart cities, but the challenge is to find clear routes toward actualising their potentiality .

In the most optimistic view, making cities ‘smarter’ also means making our basic vital infrastructures better and more reliable.

Community members have shown how our existing infrastructures like roads, transportation systems, communication networks, sewage, water and electric systems make our everyday lives possible; they connect us to each other and they help us sustain our livelihoods. However, our existing infrastructures – which we so fundamentally rely on – are particularly vulnerable in times of crisis; especially during natural disasters, wars, and global pandemics. As @Nadia, one of the community mangers describes: “I have experienced first hand how quickly basic infrastructures e.g food delivery break down when you have war eg. In the end what makes cities resilient is if people are good a[t] organising, you have emergency response mechanisms in place in government institutions that have money and training (e.g defence) and you have people with deep skills/knowledge to come up with creative solutions using tech that is self-standing i.e not dependent on complex tech and economic infrastructure” (2019). As Nadia and many other on platform have argued, in order to withstand crisis we need a holistic and well-organised model, which relies not only on trained experts, but on collaboration and the will to collective action.

Public Health, Climate and Environment, Urban Design and Technological Innovation. All of these domains at once impinge upon and rely on the stability of our basic infrastructures. An important point of future inquiry will therefore be to take a holistic view of how digital technologies will allow us to build and maintain more resilient, equally accessible, safe and sustainable infrastructures – and, importantly, how this can be achieved in a way that is human-centred and grounded in collective action.

This brings me to my final theme: thrivability.

Thrivability: How will technology allow us to build abundant and sustainable ways of living?

The @nextgenethno team and I have come to see this term as a kind of umbrella descriptor for a number of things happening on platform: the first is that it describes the community’s orientation towards the future, with the central question being, how can we both imagine and build alternatives that will enable us to ensure resilience, empowerment, security and agency? And what are the technological solutions we need to ensure this? Another part of this is a focus on ensuring greater regulation, accountability, privacy and user control, while still remaining adaptable (particularly in our design of new technologies).

These are linked to conversations around infrastructure, open source, AI, business models, the environment, various forms of labour and education, data protection and privacy (to name a few). In our SSNA there are also a lot of codes around ‘collective’ and ‘community’ and ‘public’, as well as ‘value’ and ‘common good’, which we have taken to mean that within these debates, community members are thinking about these issues from a collective action standpoint. So, ‘thrivability’ summarises these various codes in a way that describes: the act of thriving and prospering in a way that considers the role technology ought to play in our ability not only to survive (to attain livelihoods, to establish systems of support, and to access to necessities), but to build abundant and sustainable ways of living.

This month’s report has only scratched the surface of the many on-platform discussions around resilience, welfare and sustainability, and there is certainly much more to delve in to as we write up the final deliverable.

However, it is clear that when the community addresses these issues, they do so from a collectively grounded perspective of shared responsibility. This makes clear that the act of prospering (or thrivability) involves shared labour and a vision of the future which is collectively achieved (see also ethnography report 1).