Edgeryders Blog Post- El Salvador

As we continue in the process of understanding autonomy, there is an emphasis on the “to come”, on the future of where we will be. Western culture and capitalism are ingrained with a belief of progress, that each day we become more “civilized”, more “perfect”, more true to the selves that we can become. We are told that our children will always live better than we do. But as late-capitalism continues its undeniable destabilization, we can no longer place a blind faith in mere progress. There is no ability to return to the past, and so in some sense, moving forward is all we can do, but in these times of such uncertainty, we must look towards the past to remember where we have come from.

For humanity, the past has always been something to hold dear. In oral traditions, lessons were passed on to new generations by the retelling of myths and stories, a constant reminder that the struggles of today were the struggles of yesteryear. In our western culture, we maintain a memory of the past to further bolster our sense of the world. With the recent passing of Columbus Day in the US, we praise a man and a mindset that is nothing less than genocidal. We praise our presidents as bastions of democracy, albeit forgetting the fact that they were slave-owners. And recently, we passed the memory of September 11th, a day in the US that is used to justify the hundreds of thousands of deaths wrought by the US military. Yet not all memory is used for these purposes. In our own collective, we are nearing the year anniversary of the tragic death of a dear comrade. As we approach the date, there is clearly a sense of sadness, but as the grief grows more distant, his memory becomes a way to celebrate the life and vision he planted within us. There are the family memories, the anniversaries of love, of sadness, of all kinds. For so many of us, time does not function in a linear fashion, but perhaps we are always cycling between the past, present and future.

In the context of the west coast of the US on fire, the continuing superstorms hitting the US, and the growing fear of real nuclear war, I’ve come to El Salvador, to the heat and the rain, to celebrate with old friends the 30th anniversary of the town’s repatriation to their community. My trip was prior to the OpenVillage festival and I was lucky enough to be sponsored by the fellowship fund.

From roughly 1981 to 1992, the small country of El Salvador was devastated by a brutal civil war. Heavily funded by the US, the El Salvadorian government and the guerrilla army of the FMLN waged a war that tore the country apart for nearly a decade. Countless massacres of civilian populations, the initiation of “scorched earth” fighting initiated by the School of Americas in the US, and continued poverty, forced the communities of El Salvador to flee the country. In the area of Cabanas, in the northeast, many of the communities became refugees in Honduras, living in large encampments. After 7 years as refugees miles away from their own community, many populations made the decision to relocate to El Salvador, even though the war raged on. It was a decision of desperation and desire for a new way of living, courageously deciding to no longer live in fear, but rather, to forge ahead in their own land. In the camps, abject poverty was rampant, along with the continued abuses of the Honduran and El Salvadoran governments. For anyone who has been to a refugee camp, it is barely a life, let alone a place to raise a family for seven years. And so, with the war raging on in the country, the populations returned their homeland. Many were not able to return to their specific lands or they returned to a community infrastructure demolished by years of war.

In the town of Santa Marta, the first of three large contingents of refugees returned to rolling hills, pot-marked by the deep holes of U.S. made bombs. Receiving some assistance from UNHCR and other NGO groups, they were given building materials to build a community. In the 30 years that followed, a community blossomed. Being campesinos themselves, there was a lot of material support for the guerrilla movement, with many of the combatants from the communities themselves. Houses were built, dirt roads created, land was bought from the landowners and communalized, with each farmer taking care of a small plot. Educational programs such as ADES were built, with the express purpose of creating varied structures in which to support the overall social development of the community. Surrounded by conservative, pro-government strongholds, the community focused on developing its own material power and autonomy.

As the years progressed, a new generation of youth, many of whom were born in the refugee camps began to take on the struggle for autonomy. They formed groups to address needs that were present within the communities. Often undertaking the work for years without compensation, going to school full-time, and helping with family duties, they built organizations that have become vital to the community. Greenhouses for communal food autonomy, teaching new methods of agriculture to older farmers, physical therapists bringing massage and movement therapies to the clinic, youth groups working to create space for LGBTQ struggles, working against centuries old patriarchy and violence, psychiatrists working to provide communal mental health services, and finding ways to avoid the traps of mass emigration or gangs that the youth in rural poor areas always face.

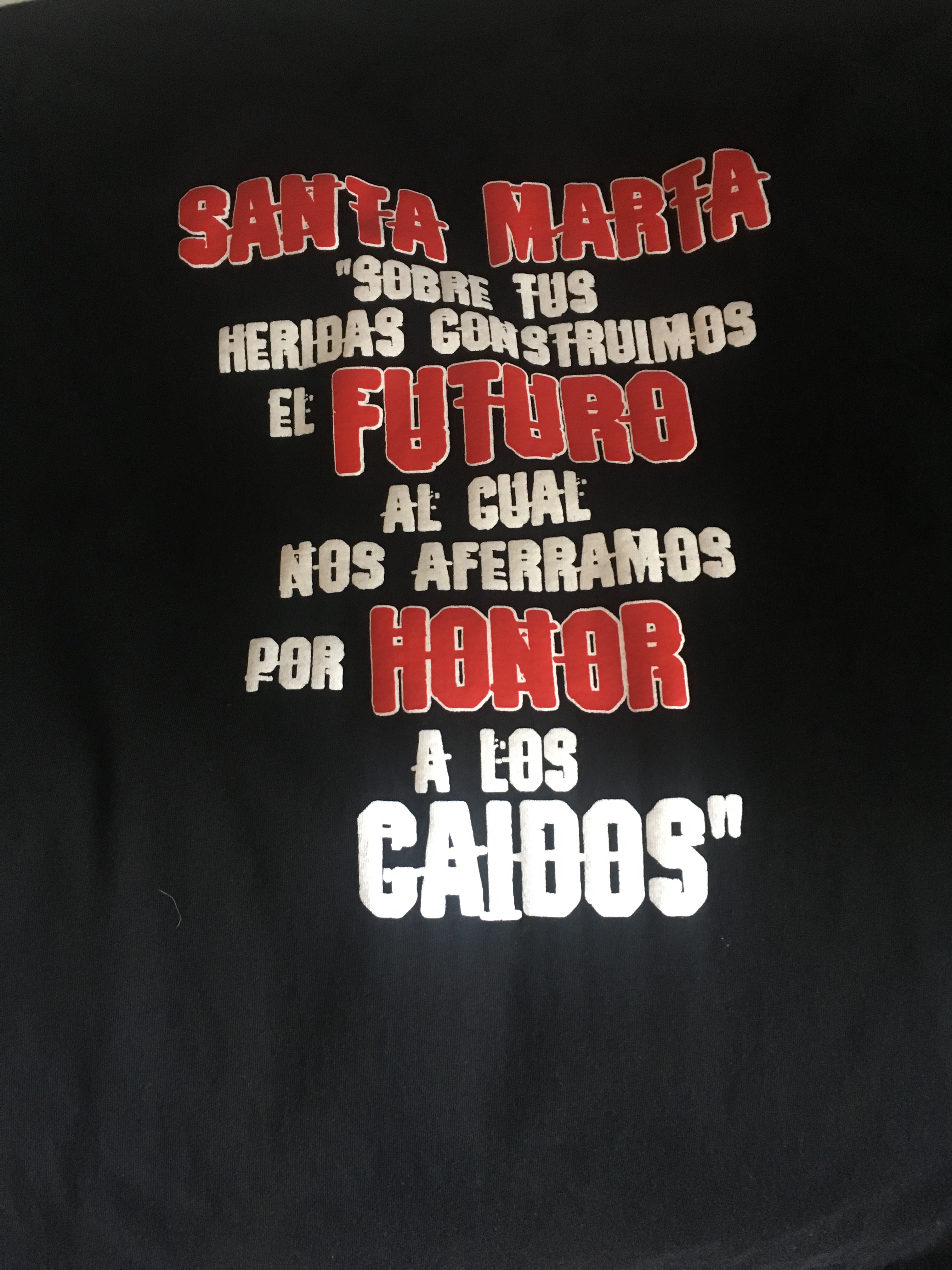

In so doing, these youth find ways to honor the memory of those who have come before. Not a blind faith, but a continuation of the vision for a new world. From the historical figures like Che, whose face can be seen everywhere in the town, to the injured combatants of the community, to the beautiful faces of the next generation running through the mud, the memory of what has been infuses the town with a strength. As explained in the theme of the festival, “with the injured, we build the future which will strengthen us by honoring those who have fallen.” The cycle of generations finds its rhythm in the ebb and flow of past and future.

The War Stories

One thing that permeates the town is a sense of connection. Not just to each other, but through history. Walking with a friend who had participated in the war as a doctor from Mexico, it becomes impossible to walk more than 10 feet without someone calling his name, a chance encounter that leads into story after story. The way the history of each other comes out humbles the mind. The man we meet walking to his farm is a dear friend from the war, who begins recalling the stories of working within enemy lines for 12 years, stealing arms from the government forces. “We never fired a shot, but used our heads,” he keeps saying, as much a lesson for us as for his younger self. The path we walk is no longer just a path in a beautiful countryside, but the “guerrilla path”. And over there by that tree, that’s “where I stepped on a mine and lost my eye”, says our friend. The stories from a fellow comrade in the US, who was doing field research in the beginning of the war in this community, recalls the 14 days he spent in El Salvador, 12 of which were under fire. His story of being a young idealist coming up against the real terror of machine gun fire, running through the hills with the community, losing track of time and his mind as fear overtook his body, still cause you to forget to breath decades later. The photos of old comrades, most of them dead it seems, the older generation laughing and at the same time holding a far away look into memory. The stories of heroism alongside the complex stories of fear taking over. And even now, the anger still felt at decisions made, sacrifices made, the way the PTSD permeates relationships often more than 30 years later.

Autonomy

Many of the young generation, those that are now new parents and community leaders, were born in the refugee camps. They returned to El Salvador with their families in the midst of the civil war. They have since developed into the leaders of many of the autonomous projects within Santa Marta. While there is some funding to these projects, mainly from community groups, international grants, and some NGO sponsorship, most of the people are volunteering many hours a week to the projects.

Five years ago I worked with CoCoSi, which is a youth led organization to increase awareness around HIV and domestic violence. They have since blossomed into a large group with more than a decade of experience of increasing education around HIV and sexually transmitted diseases, reproductive rights and sovereignty, LGBTQ issues, and eradication of domestic violence. In addition, they have been vital in facilitating access to health resources such as anti-retrovirals for vulnerable populations, including sex workers and prison inmates.

One of the larger projects is the “Greenhouse”. It is a rapidly growing group of structures at the edge of town, run by a collection of young adults in the community, with the goal of transforming food cultivation in the region and providing food autonomy to the town. They have taught themselves, through extensive travel and study, many of the diverse practices of organic farming. In a region where the use of pesticides is rampant, they strive to re-create more traditional ways of farming. Because of the economic climate, most farmers focus on corn and beans, used for some level of subsistence living but also for sale. This practice has led to an overall decrease in vegetable growing, which becomes problematic as it is coupled with the rise of processed food dependence seen all over the world. The leaders at the greenhouse recognize that most of the produce one can buy in the nearby town are the rejects from prosperous nations, such as the US, and are likely grown with heavy reliance on pesticides. So they hold classes for people to learn to start their own small scale gardens, sell most of their produce at below market rates, and hold classes for the local farmers to learn pesticide free ways of growing food.

In addition, there are a wide array of health and care related projects. Two young women run the Rehab Center, utilizing massage and physical therapy to work with many of the individuals with disabilities in the community. There is the local psychiatrist who is forming community mental health groups where people can talk about their mental well being in safe environments. Many of these projects arise from a failure of the government to provide such resources. In addition, it stems from a general understanding that the government will likely not provide such services and that they must own their own models of care and social reproduction.

Conclusion

As we move beyond the OpenVillage Festival, we must remember the paths that we have come from and work to develop a strong sense of cultural memory. The dominant culture has its own models of memory, which for many of us, no longer hold a viable future. The community in Santa Marta has been pivotal in my understanding of that failure. Instead, we must look to our revolutionary pasts to be able to reimagine a new world, a world in which we can walk together towards the idea of a “good life”.