In late August, I was asked to participate in Knowlab, “a knowledge lab to evaluate and improve the use of foresight in addressing societal challenges,” organised by UNESCO , with support from The Rockefeller Foundation , and hosted by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. To get a less filtered view of the event, check out the #knwlb Twitter stream.

In this piece, I’m going to very briefly summarize what I learned about the practice of foresight and futures studies (roughly interchangeable terms), share some thoughts about what it means to “use the future” (a key theme of the convening), and ask, essentially, “who is foresight for?” Or, in other word, Who can use the future? In a follow up note, I will share some resources I gathered at the event to put the idea of “foresight” into practical perspective, in case readers would like to use the future, too.

What is foresight?

Foresight is a practice in search of a theory. – overheard at Knowlab

Forty days ago, I had not heard of “foresight” as a profession or community of practice, which means that anything I have to say about it has both the benefit and handicap of a newcomer’s perspective. I was somewhat relieved to learn I hadn’t missed something obvious in my work to date when I read in the Wikipedia article on foresight (futures_studies) that it is a practice that has played out largely in European governance and civil society (I am based in the US). But foresight has become a global pursuit. At the event, I learned that a major university in Taiwan (I believe Tamkang University ) requires all of its students to take a course in futures studies – which means that the discipline has been incorporated into the higher education of 80,000 people in that region. One participant informed me that there are roughly 1,000 active foresight professionals worldwide.

For others new to foresight, I think it is helpful to point out that practitioners define their work in contrast to the predictions made by “pop futurists” (think Popular Mechanics or Wired magazine ). In fact, that is why you will almost always see the word “futures” in its plural form when interacting with the field.

The construction of multiple scenarios is a key method in foresight.I learned to think of foresight work as reverse engineering long-term planning and policy decisions using multiple, divergent potential futures as starting points. The promise that this approach can lead to more adaptive, resilient policy processes suited for a increasingly unpredictable world is a consistent theme in the foresight field. Foresight embraces and attempts to operationalize (or make useful) lessons learned from complexity science and systems theory, using both quantitative and qualitative social science methods. It is possible the field lacks a unifying theory, but that is likely a consequence of the fact that futures methods are usually applied in policy and institutional planning.

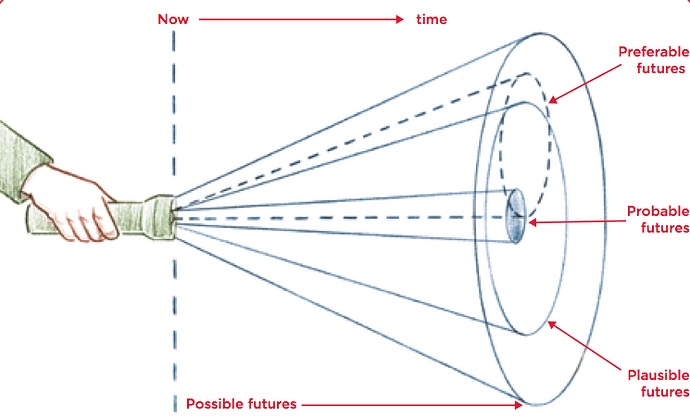

One of the simplest explanations I received during the event is that foresight makes explicit often implicit assumptions along the dimensions of:

- Plausible futures based on what we know about current systems.

- Probable futures derived from known current trends of change.

- Possible futures concerned with low-probability, high impact events (aka “black swans [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_swan_theory]).

- Preferable futures which introduce a wider scope of choice and human agency in creating best possible outcomes.

In my own work exploring the innovative edge of philanthropy, I have seen a pattern where the plausible and the probable become enemies of the preferable when discussing the field’s potential for change. In other words, “well that’s not very likely to happen” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that limits the range of design for excellence. So I felt that I had met some fellow travelers at Knowlab when I discovered that most of the energy and excitement of the field has to do with generating preferable futures.

Image source: Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow, by Jessica Bland and Stian Westlake

Using the future?

The key organizer of Knowlab, Riel Miller of UNESCO, wants more people and institutions to “use the future” in creating collective decisions today. At first, I wrestled with this phrase, “use the future.” Does “the future” exist? If the future exists, it is ephemeral, uncertain by definition, and highly contested. Meanwhile, most people are struggling to prepare for very immediate futures in daily, weekly, quarterly, or sometimes annual time frames. It was difficult for me to imagine anything so far out of touch being of much use to anyone.

Not so long ago conceptual frameworks like complexity science or “design thinking” were arcane terms, but more recently their influence is being felt in many areas. The conceptual leap I had to make to understand “using the future” is that futures exist in our individual and collective imaginations. Anticipation is a deeply human trait, and our anticipations for the future, both long and short-term, inform our daily decisions by shaping our understanding of the range of possibilities before us. In some sense, those futures use us. Riel and his colleagues are offering a “discipline of anticipation” to create greater moments of agency and choice as we enter uncertain times.

Who is foresight for?

Setting my deeper questions aside, it is clear that some people are using the future already. And those people tend to lead large, well-financed institutions that make policy decisions that affect the lives of millions. UNESCO, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the JRC are just a few examples of institutions invested in using the field of foresight in their planning and decision processes.

It is clear to me that foresight practitioners working with influential institutions are aware of and concerned about the bias an institution’s agenda can introduce into a foresight process. The idea that the future can be a “safe place for reflection and exploration” was a common theme at the event and in the literature I have scanned since. However, I get a sense that this often translates into safe places for institutional staff and advisors to explore the possible and the preferable freed from the day-to-day politics and bureaucratic constraints of their organizations.

I learned of several cases where such institutions attempted to convene diverse participants into their processes. However, I get the sense that this often means “diverse experts” or that participants are identified and recruited by experts. The institutional allegiance to “expertise” can introduce its own set of biases, and spaces controlled by large institutions and their circle of advisors may or may not be perceived as “safe” by any number of people whose input would generate value.

Expertise is a problematic construction in a networked world. First of all, the rapid pace of change calls established expertise into constant question. Knowledge is so widely available that it can be acquired and utilized without institutional credentials or recognition. Additionally, networked individuals and “small groups” can now have the kind of influence in shaping the future that was once only attainable by incorporated organizations controlling large resource pools, introducing a new element of chaos and unpredictability into the system, while simultaneously generating new areas of knowledge and expertise “on the ground” where geopolitical and economic changes are experienced first hand.

So, can anyone use the future or do foresight exercises need to originate from foresight professionals? Can foresight professionals share their tools and democratize the practice? Are they willing to lose some “ownership” of the practice, and are they open to seeing what can happen with futures imagined at the grassroots level? In any case, who is the primary beneficiary of foresight activities? If futurists want more people to “use the future,” it is incumbent upon them to articulate the value of their practices. As someone who has incorporated elements of foresight (systems theory, the power of narrative, etc.) into my work without being aware of the field of foresight and future, I am convinced that there is enormous value here. But how does it translate into a broader network of new practitioners and how do those translations return and inform the professional field?

Meanwhile, I would argue that leaders and networks outside of the field of professional foresight have been using the future quite successfully. Edgeryders is one example. A colleague of mine, Nettrice Gaskins, is incorporating frameworks of Afrofuturism and black futurism into art criticism and integrating what she’s learning into Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics (STEAM) training for young people often marginalized by traditional educational practices. I also think about Allied Media Projects, which has been convening grassroots change makers for sixteen years to leverage media and technology for social change. In recent years, AMP has taken an explicitly futurist turn, incorporating science fiction motifs and exercises to re-imagine the future of Detroit (its home base) from a technologically empowered grassroots up. In re-imagining Detroit, AMP is opening new spaces for the futures of all post-industrial cities and connecting with global participants.

In other words, the future is not the sole domain of the full-time futurists. If there is a shared goal for more people to use the future, I hope the foresight field will take a broader view of where futures expertise lives. I believe there is a lot of potential in sharing what has been learned in formal futures and foresight settings, but conversely a lot for the field to learn from those who are actively embracing and creating futures, but may be too involved in that creation to date to have connected with the formal networks of the futures field. The future is potential. I only hope that potential is universally accessible and useful.