A Witness Short Story by Sasha Ockenden

- The Interface

Loading… Loading… Loading…

It can’t really take this long, thinks Lily: any processor hooked up to the State Machine must deal with far bigger datasets than the one visualised in pulsing light on the glassy touchtable in front of her. Maybe it’s a trick, to emphasise how much advanced computation has gone into your results. The sliding scales are colour-coded: one section for her personality traits, another for physical attributes, a third for academic abilities, and the only scale which was actually interactive: her interests. She slid music all the way up to 100%; now she just needs the algorithms to certify what she already knows, and everything will become easier: funding opportunities, festival slots, Auntie Anagram leaving her in peace.

Loading…

Projected onto the back wall are the words: Welcome to the Meaningful Solidarity Dispenser! below the logo of the David Graeber Institute. If ‘meaningfulness’ is a sacred concept throughout this building, ‘solidarity’ is the watchword for the entire distrikt: the main reason, in theory, that anyone does a particular job in the first place.

An electronic marimba noise. Your results are ready, comrade Vho! Please put on the enhanced reality mask in front of you.

All jobs recommended by the Meaningful Solidarity Dispenser, a sign at the Institute’s entrance pointed out, were meaningful: they had a certified benefit to others. Citizens of different distrikts might work ‘bullshit jobs’: the priests of The Covenant, the middlemen and –women of Libria; but not here in The Assembly of People.

Lily brushes a few strands of blue out of her eyes and puts on the mask.

An ultradefinition video of vertical fields starts playing, accompanied by triumphant brass music and the artificial scent of just-ripe fruit: tart disease-resistant apples, the sweet aroma of high-yield pears.

Comrade Vho , the voiceover begins, as if announcing next summer’s ultradef Librian blockbuster, based on your unique mix of skills and qualities, and the needs of The Assembly, the meaningful job best suited for you is: Please Wait… Fruit Harvester (Berries). As this has been designated a Key Job for the whole of Witness, extra remuneration, determined by Graeberian formulae, will apply. To find out how we use your data, please see-

Fruit Harvester. The fuckers. It must have been the high physical ratings for stamina and resilience. And berries based on her height.

‘What about the rest of the list?’ interrupts Lily as the voiceover begins waxing lyrical about the camaraderie among fruit harvesters. The fruit fields are immediately overlaid with a series of job titles beside ranked glowing bars. ‘Why’s ‘musician’ right down there?’

The voice recognition software processes the question. The calculation for musician is drawn from these metrics: More charts pop up.

‘Score in Level Five Music Theory?! I was fourteen!’

No reply. Another graph shows audience metrics from her last few open mics at the Windward Platform for the Arts.

‘Oh, come on.’

Sorry. I can only respond to clearly formulated questions.

‘Fine. In that case: is there someone I can talk to? Like, an actual human?’

Loading… Loading… Junior Researcher Sally Mason is available to answer questions you may have. Please proceed to room 42B, comrade!

‘You’re not my comrade, you’re a line of code,’ mutters Lily as she stands up.

The Institute’s main hall goes more upwards than outwards, like most things in The Assembly, with a clean white marble façade that reminds her of a temple. Carved into the keystone above the entrance is a quotation: The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently. The five-second echo of the staircases seems to quieten the voices of the academics bustling past in twos and threes, far below a first-floor marble platform, a perfect spot for a gig.

It takes a while to find 42B, which exists independently of 42A or C. Lily taps on the door in precise triplets: ♪♪♪

‘Hello?’ The pale, sand-haired woman sitting at the desk has an apologetic expression. ‘Can I…?’

So much for clearly formulated questions. ‘You can. Your Dispenser thing sent me to this room. I have some questions.’

‘Sure,’ smiles Sally Mason. ‘Please – have a seat. Sorry about the mess.’

Lily stays standing. ‘So, I’m a singer, right? It’s what I do. I love it, and I’m good at it. But your algorithms are saying I should go and pick the fucking fruit. Why?’

‘They’re not technically my -’

'And why does it take so. Long. To. Load?’

‘Look,’ swallows Sally. ‘You must know we have to factor in the needs of The Assembly, as well as personal preferences. Plenty of people want to be rock stars, but we have to make sure there’s enough food to go round, too.’

‘And you must know this distrikt was literally founded by musicians.’

‘Those most suited to the arts are told as much by the MSD, I assure you. Anyway, it’s only advisory. No one’s stopping you from performing. You might just want to have a think-’

‘I’ve had a think.’

Sally sighs. ‘Our research shows surprisingly high levels of satisfaction in the agricultural sector. Picking fruit has a very direct impact on the outside world. Definitely not a bullshit-’

‘Yeah, yeah, you’re just surrounded by actual animal shit instead. Or do the fields all smell of artificial fruit like in your animation?’

‘I’m not sure what you want from me. As you say, they’re algorithms.’

‘But you program it, right? Someone has to decide how much surplus produce we need. And how many grants for artists.’

‘I think you’re overestimating how important my job is.’ The marimba noise sounds again from invisible speakers. ‘That’s technically my lunch break. But if you want to keep talking, you’re welcome to join me.’

- Revolutionary Friday

‘What about you, then?’

‘What about me?’

The angry vocalist waves a light brown hand at a huddle of Sally’s robed colleagues as they pass on the stairs; Sally hopes they aren’t listening. ‘Who’s to say we actually need academics or aethnographers? Why aren’t you out picking fruit?’

‘Well, the MSD-’

‘-which you lot designed-’

‘-gave me a higher score for intellectual than physical capacity. Every society needs researchers. Although…’ Sally stops in front of the waistcoated statue of the Institute’s namesake, clutching his seminal text, only partially recovered after the Sundering. Based on his writing style, thinks Sally, he didn’t really seem like the statue type.

‘What?’

‘Of course, it’s a question we ask ourselves. Whether our jobs risk being bullshit jobs. Mostly, I don’t think so. But when I meet someone in your situation, I sometimes wonder…’

‘Well,’ Lily shoves open the brass gate to the outside world, ‘at least you wonder. The problems start when people stop wondering.’

They walk down stone steps towards the stalls selling local produce that line the edge of Gordillo Market. A rhythmic banging in the distance is growing louder. Lily raises pencil-line eyebrows. ‘Must be Friday.’

Sally nods. ‘I went every week when I was younger.’

‘What changed?’

‘Grew out of it, I suppose.’

The noisy, colourful parade rounds the far corner of the market with an effigy of a thickly bearded man at its head, chin jutting nobly to one side, flanked by courgettes on sticks and vast, asymmetrical pumpkins. Behind them, a row of drummers keep the dancers in time. When they sense the energy starting to wear off, they pause for an electric bass to kick in, and the demonstrators roar with excitement at the intro to an early CTRL + ALT + REVOLUTION hit.

‘I’m pretty sure these guys are paid.’ Sally points at the vocalist. ‘You could start there?’

Lily rolls her eyes. ‘Who wants to be a fucking cover band?’

The electrometal chorus peaks as the demonstrators reach a blackened stone square, empty but for a few piles of scrap wood, and cordoned off with biodegradable blue tape. At the far corner stand a discreet row of fire extinguishers. A whistle shrieks and a handful of mostly young men begin hurling bottles that explode with crashes of glass, roars of flames and a cheer for each direct hit on the wood.

‘Don’t tell me you did this bit, too?’

Sally nods, smoothing the hem of her black robe.

‘Such a waste of fuel. And wood.’

‘Resources don’t only have a single function. A lot of people find the Friday Revolution very therapeutic. Even if, yes, that’s hard to factor into an algorithm.’ Sally dives into a stall and holds out her Wallet for a seaweed and horseradish sandwich. ‘So what’s your next move?’

‘I’ve had enough of this place. Your machine was the last straw. I guess I’ll go where my work is appreciated.’

‘The Migrant Train, you mean?’

‘Yeah, another distrikt. Libria, maybe.’

Sally winces out of habit. ‘Don’t you have friends here? Family?’

‘Sure.’ The bottle-throwers clap each other on the back as a People’s Volunteer begins spraying the sputtering flames with an extinguisher. ‘But I have to keep making music. Under a different system, if needs be. Maybe I’ll find more to write about, too.’

Sally takes a crisp bite of seaweed. ‘Is that something you find hard?’

‘I mean, every song here has to be political.’

‘Everything is political.’

‘God, that’s what my aunt always says about her songs-’

‘She’s a musician, too?’

Lily tugs at her blue fringe. ‘She was the original guitarist of CTRL + ALT + REVOLUTION.’

‘I see.’ Sally keeps her eyes on the blob of horseradish. ‘That must be pressurising.’

‘Can we talk about something else?’

‘Sure.’

‘Tell me what you’re working on? When you’re not converting singers to farmers?’

‘Actually, I can do better than tell.’ Sally reaches for her pocket. ‘I’m not really meant to, but…’

- The Lost Science

‘I’ve been researching jobs from before the Sundering. You know there used to be many, many more animal species? I’ve been looking into the people who studied them.’

‘Biologists.’

‘Yes, but not just for optimising wheat efficiency and so forth. There were whole branches of science dedicated to observing and categorising all these species: zoology.’ She hands Lily a mask with many more optical attachments. ‘This is ancient documentary footage.’

Lily’s vision dives into darkness. A single torchlight illuminates occasional strands of matter drifting past in zero gravity. It’s only when a distant shape flaps slowly into view – at first, it seems like an optical illusion – that Lily realises they’re underwater. The creature ripples, bird-like, right towards her face, so close that she can make out a series of black dots on its white underbelly. She flinches instinctively and hears Sally chuckle.

The spotted eagle ray, begins an old man’s crackling voice, in a quaint old-world accent, can grow up to sixteen feet long.

The camera rises through the water, which grows brighter and brighter until Lily feels herself burst through the surface in a rain of drops. The sea is clear and flat as a blank screen, and smells like Sally’s sandwich. Out of nowhere, a huge black-and-white shape breaks the surface with a deafening crash and corkscrews over her head in a tangle of wings before diving back under.

Scientists theorise this leaping may be an attempt to attract a mate; but otherwise, despite the enormous energy it requires, the behaviour serves no evolutionary function. The eagle rays do it, simply, because they can.

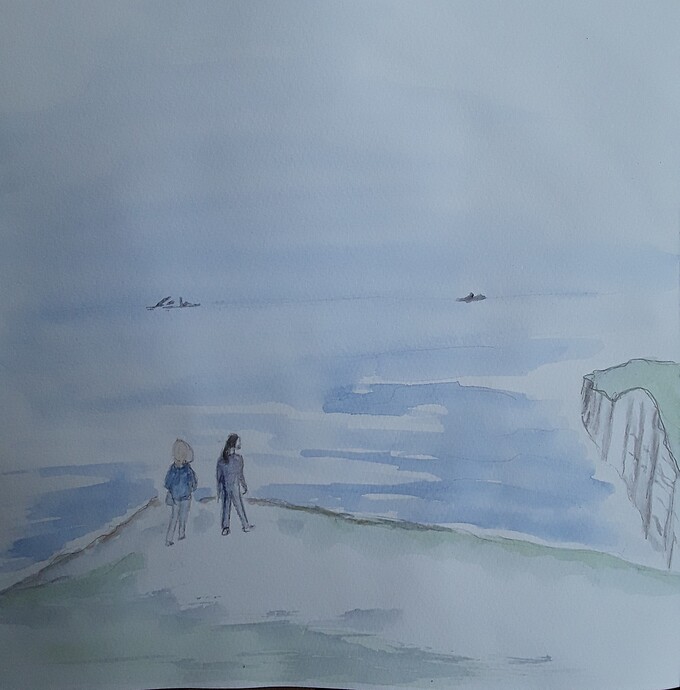

‘Do those things still exist? Out there?’ Lily gestures away from the market, towards the seaside edge of the fragile strip of floating land, one side of the hollow polygon from which The Assembly sprouts upwards. The horizon is monotonous and blue-grey: an infinite-seeming sea whose only reefs are the wrecks of old tankers, and whose bed, Lily’s been told, is littered with dead cities.

Sally shakes her head.

‘And they weren’t hunted or anything?’

‘Just studied. You can see why. Like you said: problems start when people stop wondering. Maybe one day ‘zoologist’ will be one of the MSD’s recommended jobs.’

Lily removes the mask. The air smells of petrol now; the walking revolution has dispersed into the taverns around Gordillo Market.

‘I should get back to my desk. Got some more videos to process.’

‘Sure.’

‘Have you made your mind up? About the Migrant Train?’

‘Yeah. I’ll get the first one to Libria tomorrow morning.’

‘Well, it was nice to meet you. I’ll look up your songs in the music datapool. What’s your band called?’

‘I don’t have a band. It’s just me. Lily Vho.’

‘Oh. Right.’ Sally raises her eyebrows. ‘And what are your songs about, apolitical girl?’

‘I dunno. Relationships, feelings, things like that.’

‘Sounds pretty subversive,’ smiles Sally. ‘I hope your aunt disapproves.’

‘Oh, she does. Don’t bother looking them up, though. I’m sure your algorithms can find a singer with better Music Theory scores.’ Before Sally can reply, Lily walks off, towards the sea.

- All Change

The crowd outside the station twists and turns into itself. The whirlpool in front of Sally has distinct clusters: green-robed monks clutching suitcases, gazing around; bustling engineers in navy-coloured uniforms; vendors peddling corn on the cob and hot cinnamon apple juice; tattooed traders hauling carts and trolleys; tourists, drunks – and a moving flash of electric blue. Sally fixes on it as she pushes her way beneath a giant clock and into the arched central hall. The floor is laid out in a five-pointed star, one for each distrikt, with a ticket queue at the end of each point.

She barges to the front of the Libria queue. ‘Lily! Hey. I listened to your songs last night. Your voice is, well – I’ve never heard anything like it. It has this smokey quality-’

‘Yeah, that’ll be the cigarettes. Excuse me a moment.’ She exchanges a few words with the man behind the ticket counter, who hands her a single sheet of paper.

‘I’m sorry I couldn’t help. But I think you should stay. I mean, how many distrikts have zero poverty? Almost no homelessness?’

‘Some of them have also advanced beyond subsistence farming, you know. Some of them don’t think performing solo symbolises a lack of solidarity.’ She spits out the final word as she moves towards the platform.

‘Oh, come on,’ Sally has to half-jog to keep up. ‘You’re a lone rider. That’s OK.’

‘Or a free rider. That’s how people like you see me.’

‘I don’t! Look. You know how Graeber suggested measuring meaningfulness? By simply asking people if they felt their job had any impact on the outside world. But jobs also impact workers themselves . It’s hard to measure a musician’s external impact – but in the old times, they self-reported some of the highest meaningfulness levels. Up there with surgeons, teachers and, heretical as it sounds, priests. If you feel it’s your calling, it’s meaningful. You do it because you can.’

Lily’s answer is lost in the scream of a whistle as a long, turquoise snout slides along the platform, sleek and endless, dragging dozens of carriages into the station as it brakes. The back of the magnetic train isn’t visible – but its occupants are, gazing out through windows that stretch from floor to ceiling. Some are scuttling towards the doors with boxes and backpacks as the train’s loudspeaker begins its official announcement.

Welcome to: The Assembly. Anyone who disembarks here will automatically receive a digital Wallet preloaded with a quantity of the local currency, CTRLcoin, that regenerates or degenerates towards the mean. Please note this distrikt has particularly strict regulations governing trade, import and export-

‘Permanent Migrants.’ Lily’s voice is barely audible as she points at a compartment where a group of passengers with lanyards around their necks swivel on revolving chairs, playing card games on circular tables or gazing out of the window in boredom. ‘They don’t fit into any distrikt, so they just transit between them. My best friend from school, she became one.’

‘You want to try and find her?’

Lily shakes her head. ‘Maybe that’ll be me, one day.’ She turns to Sally. ‘Why did you come here?’

Sally pauses. ‘You uploaded all your songs to the datapool. I wanted to give you something in return. Barter: it’s how all this started.’ She glances up at the clacking black-and-white board listing departure and arrival time as she digs around in her bag. ‘This is the mask you wore at the MSD. I told my boss it was defect. We’ve got plenty of spares. I loaded up a couple more archive tapes. Wait until you see hummingbirds: they’ll blow your mind-’

‘Thanks.’ Lily is staring at her.

‘I thought… it might help persuade you. To stay. We need people like you. And I mean need . When I was working late yesterday and put your music on, it made me feel…’ Sally tails off. ‘Anyway. I get it. I’m sure you’ll make a fortune in Libria, a fortune that won’t degenerate, either.’ She gives Lily a quick hug, a bird pecking at a feeder before hovering away again. ‘Safe travels, comrade.’

Sally stays where she is until the torchbeam of Lily’s black eyes becomes uncomfortable, and she lets the crowd whisk her away again in an unknowable direction, a drop of milk blossoming around a cup of tea; away from the alarm indicating that the train doors are starting to close. They must be designed to shut this slowly, like the MSD’s loading screen: an artificial delay to add weight and significance to all the decisions being taken along the grey platform, a thousand data points about to step into a paradigm shift. There’s no AI to advise which distrikt would suit them best; only informational announcements.

Finally, the monorail glides out of the station, gaining speed. As she turns away, back towards the Institute, Sally thinks she glimpses a flash of electric blue among the tonsures, helmets and headdresses of the disembarked passengers. Or, maybe, it’s just a trick of the light.