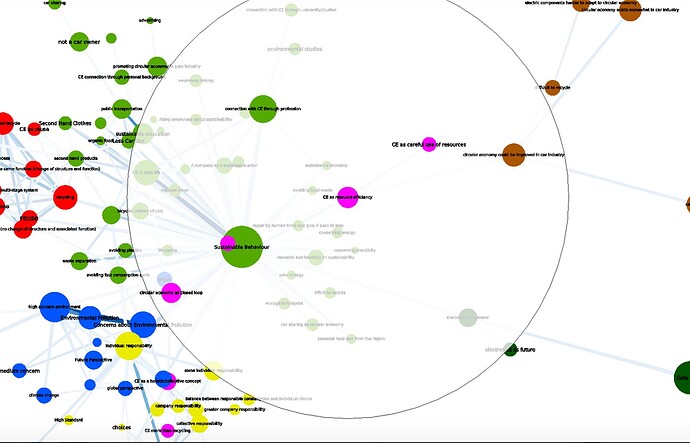

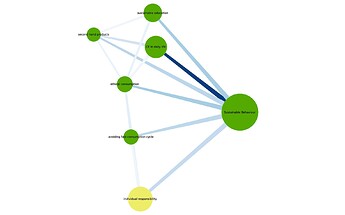

And @pykoe made this lovely modular visualization that will be paired with Insight 1 in the report:

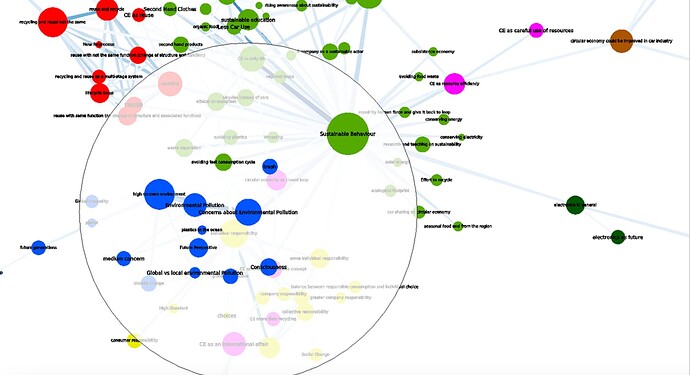

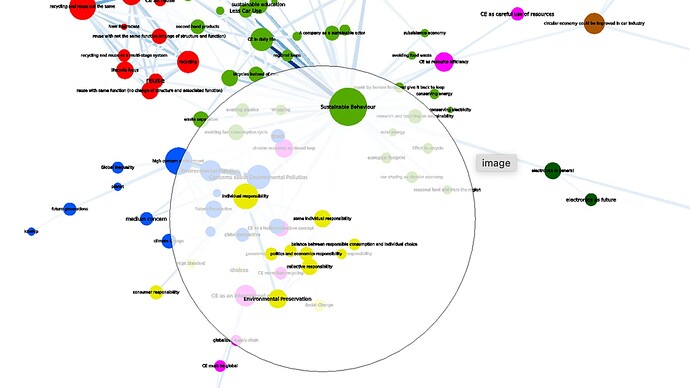

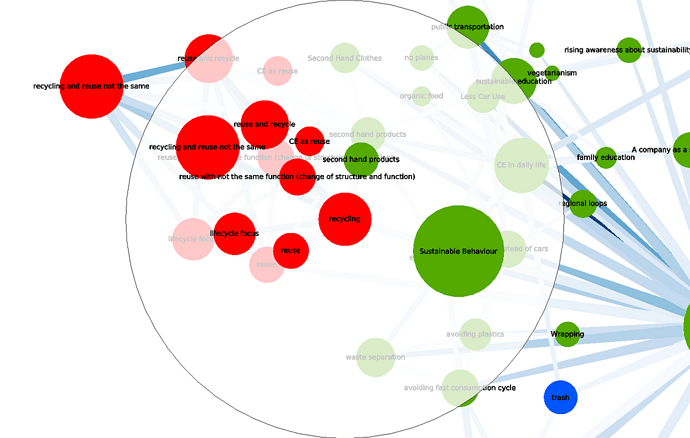

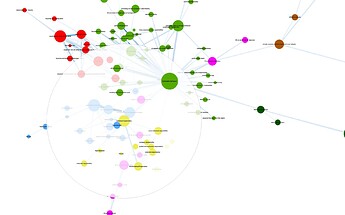

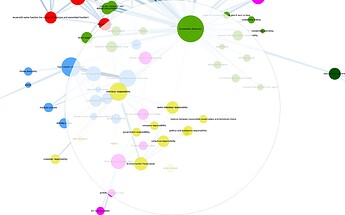

The following graphs come with the insight “social change is only guaranteed through societal commitment”:

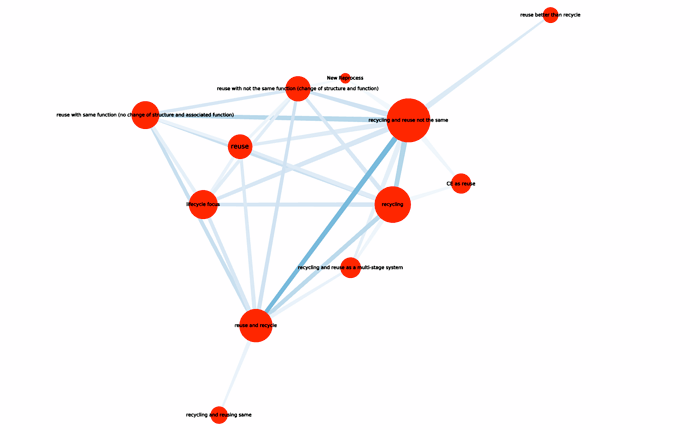

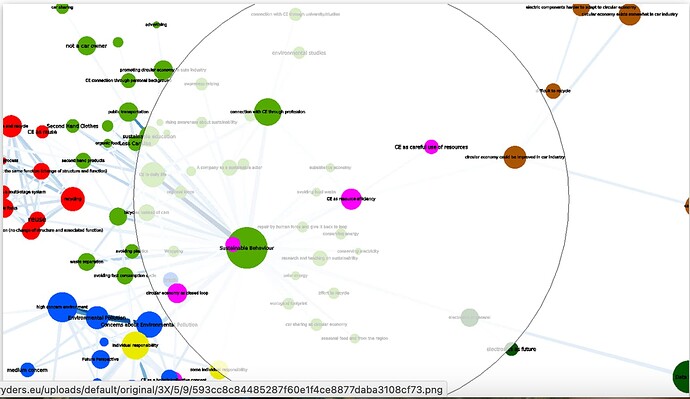

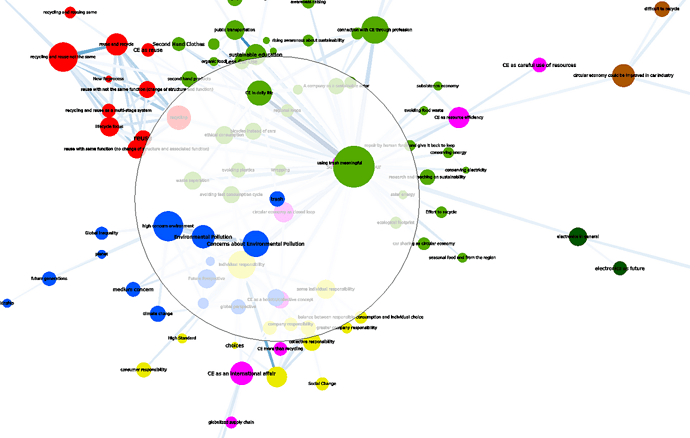

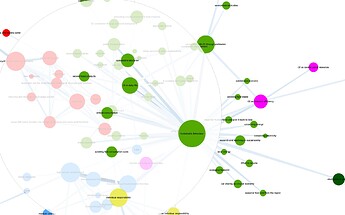

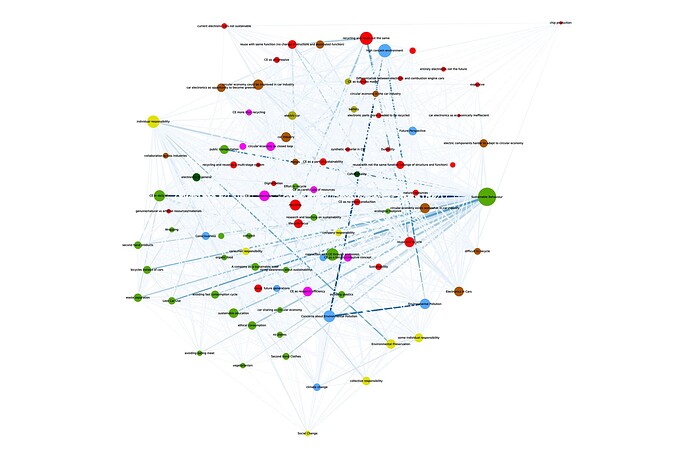

The following graphs come with the insight “circularity as a continuous result in circular economies":

@pykoe can you please also produce the following visualizations to pair with my insights 2 and 3

- Visulizations centered around the “composite materials code” and the “electric cars harder to adapt to circular economy” code

and

visualizations centered around the “individual responsibility” code, the “ethical consumption” code and “some individual responsibility” code.

Additionally, can you please make a “core values” visualization of the “car events” corpus and one for the “sustainability events” corpus.

Finally, just for the heck of it, can you please make a depth / breadth / core values set of visualizations for the entire Treasure corpus. I am not sure I will use it in the report, but I want to see what it looks like.

For each of these, can you please pair it with a short narrative explanation, the kind that @alberto did for Report 4.5 as we talked about – translating the technical aspects of grouping into the story a particular cluster is telling.

Visulizations centered around the “composite materials code” and the “electric cars harder to adapt to circular economy” code :

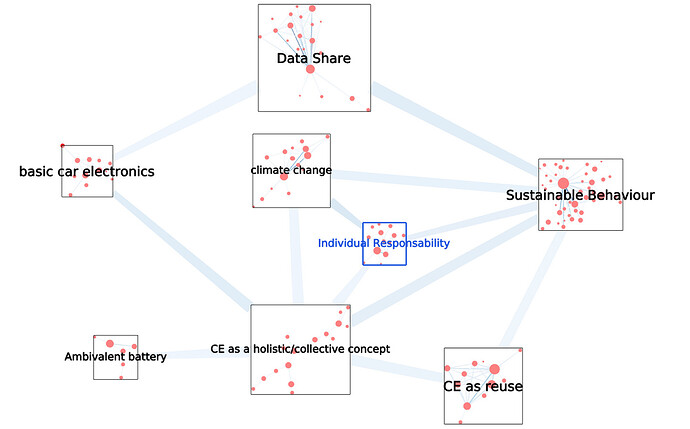

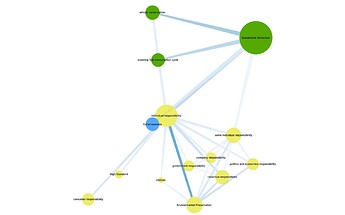

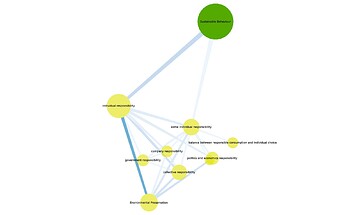

visualizations centered around the “individual responsibility” code:

focus view:

neighbor view:

visualizations centered around the “ethical consumption” code:

focus view:

neighbor view:

visualizations centered around the “some individual responsibility” code

focus view:

neighbor view:

Additionally, can you please make a “core values” visualization of the “car events” corpus and one for the “sustainability events” corpus.

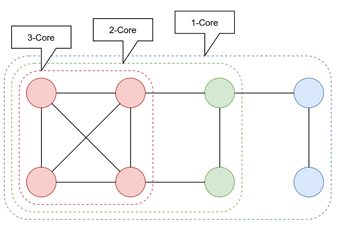

The core value is the k-cores metric that is related to nodes. This metric will indicate how much a node contributes to the strength of a community. In the following image, we can see that blue nodes with a weak value of kcore (k=1) are less important in the overall community, wherered nodes (with k-core value of 3) are the stronger part of this it.

K-Cores can be used to identify the most strongly connected parts of a graph.

Given an undirected graph G, the k-core is the maximal subgraph of G in which every vertex is adjacent to at least k vertices.[Seidman, S. B. Network structure and minimum degree. Social Networks 5, 3 (1983), V. Batagelj and M. Zaversnik, “An o(m) algorithm for cores decomposition of networks,” arXiv preprint cs/0310049, 2003]

In our case, the k-core graph, with nodes of 19 k-core is a graph of 92 codes and 1288 edges.

These 92 codes drive the entire network

Thank you @pykoe ! Did you see my other request, for you to update the visualization section pertaining to the car events in the report draft? I also tagged you there with an “assignment” in google docs.

Yes, I’m on it

Thank you! Also did you see the file @ivan posted with the gender data? Is there a way to visualize the “big” visualizations (depth, breadth, core value) so that the gendered difference in responses (if any) is visible in the images?

No I did not see the file of Ivan, could you send me the link?

Sorry it was actually sent by @owen and I see you are already invited to the thread. It’s a CSV file.

@pykoe – just checking, do you get pings when I “assign” you something in the google docs draft of the final report?

Sustainability as a meaningful vision and an activity

This section covers the insights of the ethnographic team based on analyzing the data. Therefore, notable concepts emerged in the interview transcription and coding process before the data scientists and ethnographers applied SSNA visualization and reduction techniques. These insights, combined with visualizations, help us holistically understand our informants’ discourses and perspectives. The combination of qualitative and quantitative methods achieved by combining the ethnographic insights with code visualization can offer us either validation or deepening of the ethnographic insights through the visualizations, or can reveal a divergence between ethnographic insights and emergent visualizations, which can indicate complexities and contradictions not detected by ethnographers in the first instance, and/or point to the opportunities for further refining the ethnographic research methods, e.g. iterating the interview questions to explore such divergences. Each insight reviewed below is also situated within relevant anthropological / cultural studies scholarship for a more robust context.

The first ethnographic insight considers sustainability a meaningful vision and activity, centring it as a visionary human-made product. Our informants recognise sustainability as a concept that occurs in everyday processes and procedures, which they experience and help shape. They can carry out sustainable practices in everyday life. As a result, sustainable activities are repetitive and practised in different ways and to various degrees. On the one hand, people determine the spectrum or intensity of sustainability. This makes people a subject capable of acting, whose agency, i.e. empowerment to act, determines the nature and behaviour of an individual. In the social sciences, this approach is known as theory-in-practice. Renowned representatives are Bourdieu (1977 [1972]; 1998), Giddens (1984), Foucault (1977), and Ortner (1984; 2006)), who placed the autonomous significance of a person and their actions at the centre of their works. For example, one informant responded to the question of how he would exercise sustainability in everyday life with the following answer: „(…) that I don’t fly too often, try to travel by train a lot, and also to inform myself a bit professionally about why it’s important.“

Reflections and ways to apply the forms and values of sustainable actions on an individual and societal level: action- and present-orientated, focus on concrete examples and activities in everyday life of sustainable acting. It also includes one’s own level of knowledge or the acquisition of knowledge to (actively) acquire and implement information about sustainability through education and practice and to use it for oneself and one’s own purposes. Sustainability in practice is anchored in the present but tends to look prescriptively into the future. The two areas, “private-public”, merge in sustainable visions, as sustainability becomes a lived everyday practice.

The vision has an ideological perspective that includes various approaches and combines tasks and problems relating to the environment, resources and energy sources that need to be tackled today and in the future. This consists of the self-chosen career choice, which has something to do with sustainability in the narrower or broader sense but with which one strongly identifies and which one also transfers to other situations in life. Based on the field research data, the code “Companies as sustainable Actors” shows a strong tendency to integrate and pursue a sustainable approach in everyday working life. The subsequent statement from an informant illustrates this:

“I already do it through my work by supporting sustainable technologies and also showing how companies can become more environmentally neutral. You shouldn’t always say climate-neutral, but rather environmentally neutral.“

Visionary sustainability also includes one’s own level of knowledge or the acquisition of knowledge to (actively) acquire and implement information about sustainability through education and practice and to use it for oneself and one’s own purposes. We observed that the informants were often somewhat torn as to the extent to which sustainable living can also be implemented in practice, as the following statement underlines:

„Well, I first of all, I try to live consciously, not perfectly. You can’t. I try to teach my children. Um, I take often decisions in my consumption to more sustainable products. And I work in the field of sustainability, which is also quite, quite a big step.”

Educational and awareness-raising work is another measure for actively shaping sustainability in everyday life. One informant described this below:

“[I want to have a] [h]igh impact on my kids and their friends and in a company. We have, for instance, installed photovoltaic panels to recharge the battery cars. Although I’m not driving any, there are enough people driving them around, so that would be my personal footprint and impact.”

On the other hand, however, we must remember the structure that is needed to shape and determine sustainability actively. The structure here involves an interaction between norms, values, institutions and cultural aspects that define and influence the actions and behaviour of human actors. Against this background, structures are legal or economic provisions that stipulate sustainability as a regulation, guideline or measure. For example, this can be expressed in legal norms, i.e., legislation on how companies in the automotive industry produce more sustainable cars in terms of resources, energy consumption, and working conditions. An example would be this quote from an interview: **“**So they’re already doing something. I still think that they have their [recycling systems]. I mean, we have recycling systems in our company, and they will have that, too.“

Circularity as a continuous result in circular economies

The second insight shows that circularity in the automotive industry, electronics, and environmental contexts is deemed economically feasible when it acts as a closed system to the outside world. Completing a “cycle” or enhancing current cycles requires changes or expansions within individual structures or functions of the entire system. Circularity, thus, represents an ongoing process outcome. Components such as “reuse” and “recycling” evolve constantly based on input and strategies. This encompasses sustainable actions, changing human behaviors, and evolving perspectives towards sustainable practices. For example, an informant invoked the idea that “(…) [y]es there is a whole spectrum of ways to reuse our products. Recycling is undoubtedly not the most sustainable, but it has shifted to reuse.” It’s a theory-in-practice process where not only self-defined definitions of specific procedures or processes are crucial but also moral imperatives that can influence technologically or anthropologically determined epistemological insights. Here, the circle connects descriptive action-based elements with prescriptive future-oriented ones. Sustainability serves as a driving force to close the loops. For example, one of the interviewees explained: “After all, the circular economy is more than just recycling.” Another informant weighed in: “(…) thinking and acting holistically, starting with myself, from eating to consuming to working, to inspire as many people as possible. With my being, with my existence, I want to inspire other people to live the same way.” Circular economy is a widely used concept in social sciences rooted in the Kula trade (Malinowski XXXX) and Mauss’ gift perception (XXXX). It represents a give-and-take exchange as an altruistic form of trading with each other. The concept contrasts with the ideological notion of the neoliberal market economy, which aims to maximize the interests of and benefits to the market within the limits of the law and normative order, excluding any forms of gradual commitment such as loyalty, kinship, or friendship. The concept has been criticized, reinvented, and redeveloped, particularly by Edward P. Thompson (1980) on moral economy. Based on reciprocal giving and receiving, the concept is linked to obligations and agreements. One party exchanges services with another under the conditions of a reciprocal gift. The services are only received if there is mutual benefit, which emphasizes the receiver as the primary driving force of the agreement. Therefore, such an altruistic form is grounded in moralities such as beliefs, values, and norms and imbued with an understanding of and desire for justice. The moral economy embodies a particular corpus of norms, duties, responsibilities, and values. Its moral message can mobilize forces to act. Thompson discussed the concept of moral economy, describing the rise and growing need of the working class, a labour force needed in the industrial economy. At the centre of the analysis were the ideas of legitimacy and basic assumptions of a good and just life, which led to protests by the working class. It dovetails with our gained data material about moral ideas as a prospect regarding environmental and social changes, as the following statement shows: “(…) this [circular economy] is the way to solve many problems in our world.”

This convergence of the circular economy concept with moral economy underscores how ethical principles such as justice and moral values can be integrated into economic frameworks. It presents a promising approach to addressing both ecological and social challenges, hinting at a pathway where the circular economy can tackle numerous issues in our world. By embedding the concept of the circular economy within a moral context, it offers a comprehensive perspective on sustainability and social change as the next quote demonstrates: “The circular economy. It’s an economic system that wants to replace end of life with different concepts at different levels. So not just at the product level, but also it’s relevant for cities and regions and countries. Sorry. And it’s to the betterment of the current generation and future generations. Not only money wise, but also all kinds of societal aspects.”

The final quote in this context merges circularity and change, thus serving as a bridge to the subsequent insight on social transformation: “When we start to think and operate in cycles, and no longer in a linear fashion, I have great hope that this will change things for the better.”

Social change is only guaranteed through societal commitment

The third insight shows that large parts of society have become more aware of social transformations in the areas of the environment, fossil resources, and renewable energies. This socially widespread realization is demonstrated by the summarised statements of individual informants, as, for example, this informant states, "If we do not act now, our children probably won’t have a livable future." Another informant emphasizes an alleged distinction between regions or countries: “Because I think we in the Netherlands we do a lot about it, but we also have to in the States, in Africa, that kind of countries, China." A third informant is concerned about future generations:" If we do not act now, our children probably won’t have a liveable future. Such fear and actual concerns merge with the stated need and urgency to change things, as this statement clearly shows: "Because we are already living so close to many tipping points.” The last quote to this is an appeal to change and, therefore promotes a “habit turn”: Everybody need to take up about the environment because the CO2, you know, is a carbon emission. It is really dangerous now. You cannot go like this. We need the human need to be quickly stop this happen."

The topicality and development of our planet, combined with impending climate change, is a real political concern that also affects the automotive industry and other industries.

A relevant element of this insight on social transformation awareness here is changes “on a small scale”, i.e., in individual everyday areas of life, and at an economic and political level, global and local concerns are combined and sometimes strongly separated from one another. The individual power to act is sometimes seen as a potential for empowerment, sometimes as powerlessness. One informant states, “I would say it’s like middle tier of responsibility because those personal choices won’t revert the environmental issues.”

Our data analysis shows that a collective, solidarity-based demand for social and environmental change is needed, which must be multidimensional to achieve more significant and sustainable change. Hope, as highlighted by Freire in 1992, plays a crucial role in shaping the course of social change within a collective and holistic perspective.

Global dynamics (such as value chains, partnerships, or agreements/contracts in producing car electronics) need to be reshaped in favour of social and environmental benefits as this subsequent quote sums it up: “It’s definitely international. It affects all of us, especially with just the level of global trade that takes place in modern day. It’s something that needs to be combated together and the responsibility that needs to be assumed by everyone for it to function and change to take place.”

However, the collective understanding is often ambiguous and - although defined as “we” - no holistic and globally all-encompassing unit is formulated. Although the “need for global action” mentioned above is clear and broad, there are also clear distinctions and demarcations of an intersectional dimension (about social origin, gender and race). In the social sciences, such an argument is in critical and postcolonial theories, where ruptures between the global South and North are undeveloped or developed. It would also be time to change direction here and demand accountability (Roodney 2018 [1972]). The “we” is then problematic and does not fulfil their demand. Following up on this, in a social contract accountability is owed to both the weaker and the powerful actors in society. This unequal perspective requires holding all parties responsible for their actions."

Decision-makers in realms such as politics, business, and industries such as automotive have the responsibility and obligation to establish a standard. Policies and legal actions are increasingly crucial tools for oversight and responsibility, requiring constant refinement, enactment, and supervision.

The final quote encapsulates the idea of holding state institutions, politicians, and influential industry figures accountable, while also demanding a framework from them that fosters social change and allows for practical implementation. “We are very short sighted in in making decisions. So I think we need more direction guiding and sometimes ruling from more governmental authorities.”