For the past three years we at Edgeryders have been working on a large-scale ethnography of the Next Generation Internet (NGI), under the aegis of the NGI Forward project. This turned out to be quite challenging, but also very rewarding in its own way. Ethnography evolved to study the culture of well-defined human groups, and was first deployed in the context of anthropological research on indigenous communities. Definining rigorously those groups has its own challenges, but defining the contours of “the NGI community” can be daunting.

A maximalist way to go about it might be to consider that anyone impacted by important development in the Internet’s architecture, functionality and business models is part of the NGI community. But that means everyone in the world: the Internet is such a pervasive infrastructure that no one is unaffected by sweeping changes in how it works. A much more restrictive way to go about it is to consider the set of professionals that work actively to influence the shape of the future Internet: national/international policy makers, large tech company, standards’ bodies, lobbyists, consultants, pundits, specialized media. But that was no go, too, because the European Commission, in funding the project, had made it crystal clear that it wanted civic engagement beyond these usual suspects.

So, we set up to involve the communities at the periphery of the debate on the future Internet: hackers, open source enthusiast, tech-savvy users and educators, smaller businesses, privacy activists. In so doing, we hoped to provide a useful counterpoint to the points of view of NGI professionals and of specialized media. We encouraged them to discuss with one another on a dedicated forum, NGI Exchange; we used this online space as a meeting place for the community that was emerging from these discussions. Their posts on the forum (evenutally, over four thousands) became the corpus of the ethnography we were trying to produce.

This certainly worked in returning the diversity of voices of those engaged with the Internet. From citizens concerned about the use of digital technologies in the COVID 19 pandemic, to legal scholars attempting to challenge hidden biases in the deployment of machine learning algorithms, to teachers wondering how to educate their students on open source, we heard from people from every walk of life. This resulted in a digest of the best contributions to the forum, in a curated form for the reader who takes an interest in hearing directly the voices of the community; and in an ethnographic report, to aggregate and summarize every single contribution in a big picture. This was not trivial: most ethnography journals will publish studies based on 6 to 20 key informants, and we had nearly 350. In order to zero in on the most relevant information in the corpus, we had to use semi-quantitative methods, borrowed from graph theory, to augment the ethnographic analysis.

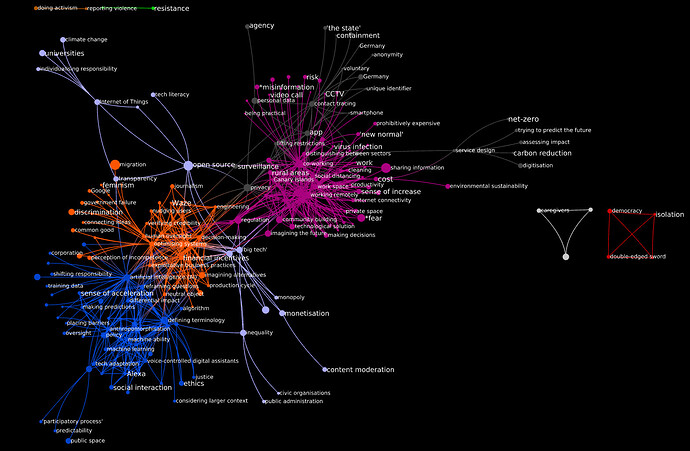

This algorithmically assisted selection of key content resolved in a high-level map of NGI topics. These were not uniformly co-occuring with each other, but clustered in only four high-level “umbrella topics”: the Future of Work, Data, Privacy, & Control, Resilience, Welfare & Sustainability, and Artificial Intelligence. Our main findings are that our community, the unusual suspects around the debate on the future Internet, point to a need to negotiate the Internet’s impact on human life. To do this, they return to the inescapable fact that the Internet is made not only of technological artifacts, but also of people. Almost nothing, they claim, can be solved by technology alone. Almost no good solution is only technological, and some good solutions are not technological at all. From here, they proceed to envision a future Internet where humans are at the centre, and not only as individuals (let alone consumers), but also as communities. Online spaces (for work and socialization) are great, but to be effective and human-centric they need offline spaces too. Regulation of big tech is sorely needed, and so on.

Mapping the NGI debate: the giant component of the network of ethnographic codes resolves clearly into five main clusters of nodes

During this work, we realized that our colleagues at the Universities of Warsaw and Aarhus had been getting to similar map, using different data (for example, articles from specialized media and social media) and different approaches (for example natural language processing), but with striking similarities in how they, like us, had to alternate interpretation and automated analysis as they moved from data to results usable by decision makers in government and business. We decided to document our respective research processes in a comparative fashion, and this resulted in a methodological paper.

Comparing methods to discover umbrella topics in the NGI debate

All in all, it’s been quite the journey! We are happy and proud of having been part of it, and humbled by the great work of our partners in the project, especially NESTA as the coordinating partner. My personal thanks go to our skipper, principal investigator Katja Bego. We look forward to a more human-centric Internet, and aspire to continue to contribute to building it.