The State argued that SyRI was necessary for preventing and combating fraud in the interest of economic welfare. The Court agreed that this is an important interest of society. However, the State failed to demonstrated that SyRI was a proportionate means to reach this goal.

That depends on what we mean by “a good prediction”, @antonekker. If we are happy with being “good” (outperforming randomness) at the aggregate level, we might need very little data. For example, in predicting the outcome of football matches, the simplest model “the home team always wins” does (a little) better than random. Hal Varian (Google’s chief economist) a few years ago went on record saying “if you have 99% correlation, who cares about causation”, or something like that. But this extra performance only applies to predicting a whole lot of football matches (the population), while being useless if you are trying to predict one match in particular.

I think @katejsim worries that prejudices outperform randomness. If you don’t care about fairness and the rights of the individual, you could indeed predict that the poorer neighbors would have more social welfare fraud than rich ones. But this would come at the expense of treating poorer individuals fairly, and, unlike with football matches, it would end up reinforcing the conditions that force those people to apply for welfare in the first place.

Interesting point.

Taking the possible consequences for citizens in account, the predictions should actually be much better than just ‘good’. If 2% procent of the outcomes are wrong, this is already effecting a large number of people.

This raises the question if decisions by government about fraud can ever be left to algorithms alone. Maybe, human interference should be mandatory.

One of SyRI’s stated goals is to find “tax fraud.” Tax fraud, as a category involves every strata of income and society. But did the government only train SyRI’s onto more marginal neighborhoods?

I like this argument. I guess the proponents of systems like SyRI would reply that existing non-algorithmic systems are also bad at predicting fraud (worse, in fact). So, you would need to put a premium on fairness over effectiveness in order to defend the position you had in the SyRI case.

Exactly. It’s not just about the rigor of the predictiveness of the system, but also the immediate and far-reaching consequences of error rates: false positive means that people who need welfare benefits don’t receive it.

Also, hard to hypothesize likelihood of welfare fraud in rich neighborhoods lol. To be fair, SyRI’s scope was for both welfare and tax fraud, but I maintain that the context/scope/impact of tax fraud in poor neighborhoods are incomparable to affluent ones.

Good point. One could ask why SyRI was not used in the richer neighbourhoods. That might actually result in much more fraud being detected. Of course we didn’t make this argument in court. Rich people have a right to privacy too

True, but ‘existing non-algorithmic systems’ basically depend on human decisions. This makes it possible to talk to a human being. Algorithms cannot yet explain their reasoning.

Ok, but if you catch one rich person for tax evasion, that might be equal to ten cases of social security fraud.

That’s what I mean!

Ha. The expected value of catching an offender correlates positively with the income of the people being searched. I guess if you train an AI on the sums claimed back, rather than on the number of offenses, it will zero in on the rich folks. ![]()

I need to go, but thanks so much Anton for your time. This was very, very interesting, I’ll think about it more.

As I recall, Article 8 also gives some protections from profiling in the form of ‘fishing expeditions’. It was not part of your argument, but in the future when or if they reinstate a more transparent version of SyRI, it could perhaps be a valid argument.

Thanks everybody! I need to go as well. See you later…

In fact we did use this argument. We argued that a system like SyRI can never meet the proportionality requirement because it is an ‘untargeted’ instrument.

Really have to go now. Feel free to send me an email, should you have any questions in the future: anton@ekker.legal

Thank you everyone for the generative discussion, especially @antonekker for sharing his experience and insights with us! Do keep up the discussion/comments/questions with each other, and please feel free to reach out to Anton directly.

The AMA with Anton Ekker: an overview and some questions

Anton Ekker, a lawyer, fought in court the use of the Dutch government’s risk scoring algorithm to detect welfare fraud. We at Edgeryders organized an AMA with him to learn more about the case. This post summarizes the discussion we had during the AMA. The full discussion is above it.

At the end of the post, you will find a list of questions raised by the AMA, but left without an answer. Can you help us answer them?

Why the algorithm was deemed to be unfair?

The court observed that SyRI was not comprehensively sweeping the Dutch society. Rather, the government aimed it at poor districts.

In his book Radicalized, Cory Doctorow has a great explanation of why AI trained on law enforcement data tend to be biased:

“Because cops only find crime where they look for it. If you make every Black person you see turn out their pockets, you will find every knife and every dime-baggie that any Black person carries, but that doesn’t tell you anything about whether Black people are especially prone to carrying knives or drugs, especially when cops make quota by carrying around a little something to plant if need be.”

“What’s more, we know that Black people are more likely to be arrested for stuff that white people get a pass on, like ‘blocking public sidewalks.’ White guys who stop outside their buildings to have a smoke or just think about their workdays don’t get told to move along, or get ticketed, or get searched. Black guys do. So any neighborhood with Black guys in it will look like it’s got an epidemic of sidewalk-blocking, but it really has an epidemic of overpolicing."

“It mat be unfair, but it works”. Or?

We had an interesting discussion about the effectiveness of SyRI. The court itself admitted that

Such effective prediction is probably unadmissible in court, because it is not based on “substantive merits of the case”, but rather on observable variables that correlate statistically with those substantive merits. We discovered that this effectiveness was not neutral, but deployed disproportionately against disadvantaged citizens in another dimension:

If you train an algorithm to maximize potential tax fraud, it will almost certainly zero in on rich people. This is simply a feature of the mathematical landscape: the higher your gross income, the higher your potential for tax fraud.

Moreover, if you trained the whole of SyRI to maximize the overall monetary value to the state (social welfare detection fraud + tax fraud) it would probably still target the rich, because

Even if it works in the aggregate, it can still be very bad for individuals

AIs are trained on datasets, and evaluated on how well they perform on average. They do not need to be accurate, they just need to be a bit more accurate than the alternative. In machine learning, the alternative is normally standardized to random selection. To be useful to the Dutch state, SyRI only need to detect more fraud than checking citizens at random. That’s a low bar to clear.

The thing is, the consequences of a SyRI error could be dire for a person. Defending yourself against allegations of fraud costs time and effort, and often money.

Open questions

The AMA session raised more question than we could address in one hour. Here’s a stab at listing the remaining loose ends. Do you have any information or want to share an opinion about any of them?

1. Standards for how to prevent bias and discrimination

2. A trustmark for AI

3. European-level protection against AI abuse by government

4. “They keep coming”

The SyRI case is a bit special, in that one of the parties was the Dutch state. The state is subject to the law… but, unlike the NGOs on the other side of the case, it also makes its own laws. So, it does not have to win in a court battle; another way to win is to simply change the law.

Given all this, can human rights activists really win these battles in the long run? If not, what else can be done?

Check out our next AMA:

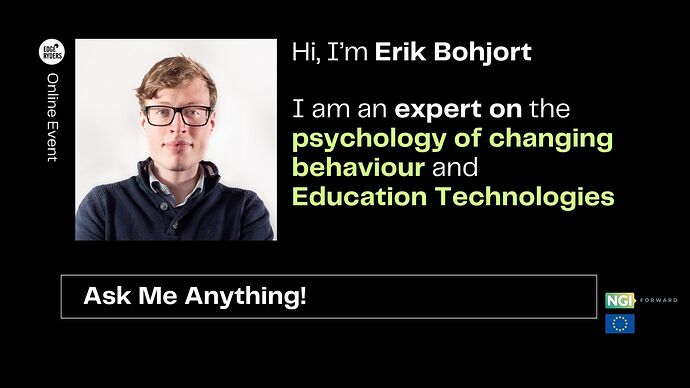

On the 9th of December 18:30 to 19:30 psychologist Erik Bohjort joins for an AMA.

- Would you wish you could change your own behaviour sometimes?

- Are you wondering how much technology is actually ok for your children, and if and how they can learn with digital tools?

- Are you developing an app, website, project to change and improve the world, and want to know how to best influence behaviour or how to nudge?

- Do you have your own insights and/or issues (2020 has been hard on everyone…) you just really would like to discuss with a psychologist?

Then you are in luck!

Erik (@Bohjort) is a Psychologist at PBM working in the field of Behavioural Insights.

His background also includes experience as the Head of Research at Gimi AB (an educational FinTech application to teach financial literacy to children) and as a Psychologist at Akademiska Sjukhuset in the Neuropsychiatric Unit.

His research explores topics such as:

Behaviour change, Digital education, Behavioural insights, Nudging, Psychology

For one hour he will be available to answer all of your questions and engage in discussions, conversations and maybe even a bit of therapy with you.

Register here to get a reminder before the event and join the AMA chat.

The live chat will happen here, where Erik personally introduced himself:

Bumping this up because the Dutch are at it again. Now they use dual nationality as a proxy of likelihood of fraud by parents receiving child care subsidies. “Ethnic profiling is easy to do with proxy variables”, as someone noted on Twitter. Very difficult to change the logic.