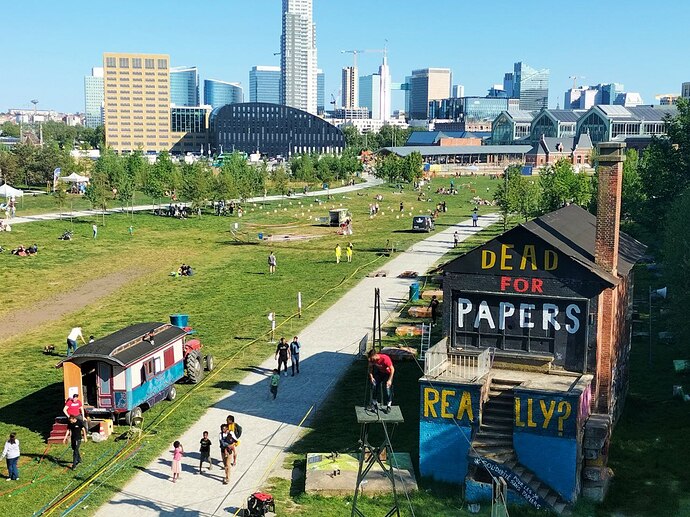

Solarpunk Brussels. Photo by me, CC0

I am building a cohousing. It’s crazy, I know: it is going to take up a lot of my time for several years. It would be far more efficient to just buy an apartment and be done with it. But “efficient” is not where the action is, at least not for me. Apparently I am unable to stay away from the idea that modern living is too atomized, and that someone should do something. In fact, I should do something. I first became interested in cohousing about fifteen years ago, back in Milan. @simonedb was already well on the path, and he had fascinating stories to tell. Ten years ago, when @nadia and I moved to Brussels, we decided to live communally – rent a big apartment and share. I never looked back.

But I did look forward. In 2019, supported by Edgeryders and EIT Climate-KIC, my colleagues and I, led by @matthias, started looking into what a more social rural and urban living (the latter being what interests me personally) might look like in the era of groupware and open source tech. We spoke with architects and community organizers, technologists and city leaders; we held brainstorming workshops and took part in socializing events. What we found is a longing for three things: environmental sustainability; a deeper sociality; and non-market coordinating mechanisms (run the building rather than hire a professional; grow some of our own food, produce our own solar energy, etc.).

In a way, this does not make a lot of sense. What difference is it going to make if your condo is bulk buying organic-and-local veggies? You are still going to live in a world driven by global logistics and Monsanto and Blackrock. The planet is still going to burn and drown, and you are still going to breathe polluted air. Sociality, sure, it’s nice to be in good terms with your neighbors. But again, it’s a tough world out there, there’s homelessness and vulnerability, and the climate refugees, so that you can only keep up your communitarian paradise at the cost of locking yourself behind a gate. And as for market mechanisms, we are told they are efficient, and they are: building your own cohousing means that it takes five years before you can move in, and in that time it will basically be like running a company. It is far simpler to turn to the real estate market.

And yet, those choices feel right. Right enough, indeed, that in 2021 I myself decided to band together with a small group of Brussels-based people (which includes @Lee and @manuelpueyo), start a not-for-profit as a shell for the project, put my shoulder to the wheel, and push like hell. Why do I bother? This question has troubled me a lot: it still does. But I do have an answer now: building a cohousing is like building a different world within the world we have. And, in terms of that different world, the choices of green, social, and non-market make plenty of sense. Most cohousings I know incorporate elements of solarpunk, with its optimistic-yet-realistic approach, its ethos of self-actualization in relative harmony with the planet and other people, and its “luddite hacker” approach to technology (on which Cory Doctorow has much to say).

By now, I have done research on solarpunk art, literature and even economics, and I think I understand it better. It is utopian thinking, to be sure, but in their defense, solarpunks have bothered to chart a route that will take us from here to there. Also in their defense, when humans are by some miracle left alone for a few precious years by late-stage capitalism’s artificial scarcity, they tend to create distinctively solarpunk-looking physical objects and social arrangements, like the private-yet-open-to-all garden in Brussels in the photo above. I see solarpunk everywhere, from Boeri’s vertical forest to the depiction of Wakanda in the Black Panther Marvel movies, to the plethora of Burning Man-like events all over the world. It’s like the world is bursting at the seams, and it wants to be solarpunk now. And this is before you even start talking about the climate crisis, which, believe me, I do.

Solarpunks are quite realistic. They are obsessed with organization, and have recruited existing organizational models that they like, or come up with new ones, to do (in theory) just about anything, from space programs to, well, building a cohousing. They are big on cooperatives, and social capital underpinning highly efficient handshake deals; not so big on complex financial products and sueing each other. They are also big on collective intelligence, building strong groups and making the most of everybody’s knowledge and skills. This tends to produce intelligent decisions, but also to be slow and frustrating. To mitigate the problem, solarpunks have co-opted or developed, frameworks like sociocracy, techniques like Nonviolent Communication, and a thousand hacks to make decision-making more efficient while still giving everyone a voice.

They are also more risk averse than your typical capitalist enterprise: which makes plenty of sense, because in their world a bankruptcy is not only a legal procedure, it is letting your community down. This is very good for me personally: our own cohousing is a seven million euro project, and building the group is much like starting a company: it’s not so important that your partners are your best friends, but it is important that they are rock solid, and that they have your back, as you have theirs.

In my experience, most people who sympathize with the solarpunk movement and most people building cohousings are, in a sense, similar. They – we – are nostalgic for a different world, that never existed, and likely never will. But in a sense, this does not matter, because the solarpunk utopia is fractal: it can exist in small things, like a community garden or a cohousing. And those things, we can build. Thanks to all this organizational wisdom, we can even build them to survive and thrive within the world we have, while still hoping for a better one.

And so, we will. Our cohousing is called The Reef, in tribute to the diverse webs of cooperation and competition that exists in real coral reefs, and also as an act of remembrance should all coral reefs in the world die, which is not unlikely at all. If you want to talk to us, or even wish to join us, get in touch.