OPENCARE started in early 2016 with three objectives in mind.

The first: explore the potential of communities to design and deliver care services. Citizen experts and patient innovators were coming up with exciting new products and services for care. What was going on?

The second: explore the implications of all this for policy. Care is high in the policy agenda. Health and social care services are expensive, and getting more so. What opportunities arise when informal networks of patient innovators step into the arena? What threats?

The third: generalize from the provision of care services to the provision of anything. Care is important. But the engine powering community provision of care is, at the end of the day, collaboration. And collaboration cuts across all domains. In the care domain, it is hard not to see collective intelligence at work. But what is that, exactly? How does it work? Can we detect it, measure it? How?

Here is what we learned so far.

1. The potential of communities to design and deliver care services

Communities have great potential for providing care. Reading through the hundreds of stories we collected, one gets the sense of a swarm. Initiatives everywhere, most of them small, addressing the full spectrum of health and social issues. Powered by collaboration, they achieve incredible results.

In Greece, they build tens of clinics with no money, no staff and no legal existence to treat, for free, anybody who has lost their right to public health care. In France, they develop a cheap ultrasound-based stethoscope. In the USA, they create an open source method to produce cheap insulin. In Romania, they form a network to deliver anticancer drugs unavailable in the country. Public health care struggles with financial constraints. Business focuses on serving those who have money. But everywhere we look, smart, generous communities step into the breach to care and give support.

Many of them – most, even – contain elements of innovation. Innovating communities take full advantage of small size, independence and closeness to the problem. Taken together, you can see them as a decentralized system that innovates in all directions at once. A bus kitted as a mobile studio for trauma counselling. A peer-to-peer alternative to 911. An ultracheap modular system for people in refugee camps to build their own furniture. The list goes on and on. Community innovators are “crawling the solution space” in a way no organization could.

2. Implications for policy

Community provision of care services carries benefits for social welfare. The “wisdom of the crowd” in care trumps public- or private sector provision of care in certain scenarios. Based on 19 case studies, we identified four such scenarios.

- When information is dispersed. This happens, for example, in websites where patients can compare the side effects of medication. Crowdsourcing of information provision works well in these cases.

- When the conventional systems of provision fail. This happens in emergency situations (the "refugee crisis" and in countries hard-hit by systemic crisis. Locally organized clinics and health care provision have flourished in these cases. These initiatives often need a strong subculture to motivate participants, and can be hard to scale.

- When participating in producing care services is itself beneficial. This happens with many services around mental health and addition.

- When "evasive entrepreneurship" reduces the innovation costs introduced by regulation.

3. The inner workings of collective intelligence

We learned four main things about how collective intelligence in action.

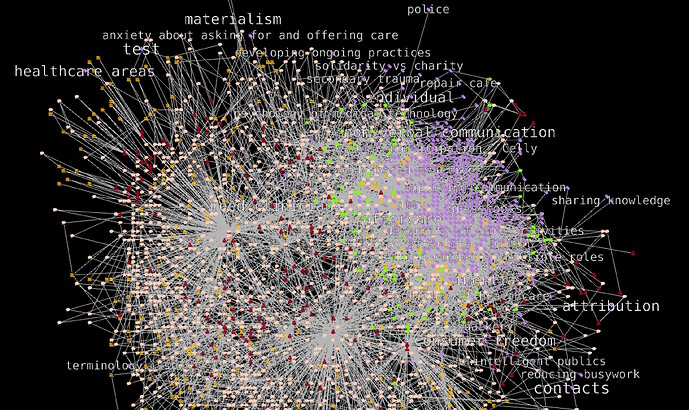

- Collective intelligence has structure, and a network science approach can detect it. We seek collective intelligence in interaction: by constantly improving on each other's work, humans give rise to a system which is smarter than each individual participant. There are two main kinds of interaction in opencare. The first is social interaction – who interacts with whom in the online conversation. The second is semantic interaction: which key concepts interact with which. Combining the two, we get a well-defined semantic social network of the opencare conversation. From semantic networks we understand how participants see open care as a group. From social networks we can "grade" individual contributions: denser interaction means more scrutiny, thus more reliability.

- It's all about humans. Many of the solutions and needs expressed by participants are non-technological. Community provision of care services needs humans: more, better prepared, volunteers. People prepared to teach each other skills. Therapists to help volunteers in need of trauma support, and so on. This suggests that the highest-impact technologies are technologies that help bring people together, share knowledge, and distribute human resources across different care contexts. These technologies are connectors: they help string together and coordinate human efforts. Their role is consistent with our vision of collective intelligence as interactional. In contrast, technologies that attempt to replace humans are never invoked in opencare.

- Collective intelligence dynamics can be encouraged with (some) success. OPENCARE was able to start and steward a large scale conversation from scratch. Though this is only one of opencare's activities, we have met our quantitative goals one year ahead of schedule. The online conversation alone has over 200 participants, 2,000 contributions and 400,000 words. We achieved this by deploying techniques borrowed from hacker culture rather than corporate communication.

- The interface between online and onsite collaboration environments is a single point of failure. All-online (OPENCARE web platform) and all-onsite (lab, workshops) collaboration develops naturally enough. In contrast, we found it difficult to cross the online-onsite barrier. For example, it is hard to report the results of onsite workshops in such a way that they feed into interaction online. Learning to better connect online and onsite environments would result in stronger collective intelligence dynamics.

4. Things we did along the way

This journey took us through interesting waypoints. Among them:

- Build an interactive dashboard for studying semantic social networks: http://164.132.58.138:9000 (University of Bordeaux, Edgeryders).

- Provide expertise and facilities to develop and prototype a device for monitoring reduced-mobility individuals. The device, called InPe, warns the caregiver when the patient falls over (WeMake).

- Co-teach two design courses. One at Universität Der Kunst Berlin (Edgeryders); the other at Domus Academy Milan (WeMake).

- Organise onboarding workshops and community events. These took place in Milan (WeMake, City of Milan), Brussels, Thessaloniki, Berlin and Galway (Edgeryders), Bordeaux (University of Bordeaux), Geneva (ScImpulse) and Stockholm (Institute for Economic and Business History Research).

- Contribute to defining good practice for publishing ethnographic data as open data. As far as we know, no one has ever published open data of this kind before.

- Publish a paper: Cottica, A. (Edgeryders), G. Melançon (University of Bordeaux) and B. Renoust, 2016, “Testing for the signature of policy in online communities”. Studies in Computational Intelligence n. 693, Cham (Switzerland).

- Be ourselves open. Our main coordination channel is accessible to all on the open web. We published the opencare proposal with an open license.