The interesting thing about writing a summary of ethnographic findings at this stage is that they do not altogether differ from some of our original observations. The community seems to consistently find similar issues important. Whether that stems from the fact that these kinds of observations appeared first and inspired similar posts, or if these issues are just universally important to the community remains to be seen (and I’d love to hear your theories!). New threads are constantly emerging as well, dovetailing with existing stories and painting an even richer picture of the ways people care for one another in our current precarious climate. So I’ll outline a few important connections that I’ve seen so far. Some loci of conversations are as follows:

1. Resilience in the face of Crisis

Crisis has been a key theme throughout our time together, whether it be the financial crisis in countries like Greece or the refugee crisis that has led to mass migration. Community members have been thinking up all kinds of ways to maintain resilience, trying to balance preservation of old ways of life (like neighbourhoods, or safeguarding the elderly’s stores of valuable knowledge) while being open to new community members arriving from other shores (through intercultural exchange, and overcoming language barriers). The interesting thing to me as an ethnographer has been the ways in which, even though the two efforts at first glance may seem opposite (protecting against and embracing change), the same strategies are being used. Bringing strangers together through the fostering of social events or the creation of shared public space, making spaces for education and skill sharing – these are the ways that communities in crisis band together and show solidarity for one another.

Crisis also comes in the form of precarity: decreased opportunities for employment/labour, rising housing prices, and our youth seeing a lack of a future for themselves. These kinds of crises have been answered by community-based care, the umbrella for so many interactions that have been documented on Open Care: through co-habitation, skill-sharing and skill-building, building or repurposing space for living, and many other creative living arrangements. Places are at the heart of communities, whether those places be neighbourhoods or homes, cities or rural areas. It has been exciting to see connections across disparate geographical terrains present (sharing drugs across national borders, or online support groups), and international networks coming into being — these have lead people to meet up offline, and to strengthen the spaces in which they live and work. Despite claims that the internet is radically removing the need for place, offline spaces remain crucially important to communities in Open Care.

Crisis takes another form as well: climate change and pollution have created concerns among community members, prompting the need for greater resilience in the face of natural disasters and environmental disruptions, and creating sustainable solutions has been a key factor in a lot of conversations across topics.

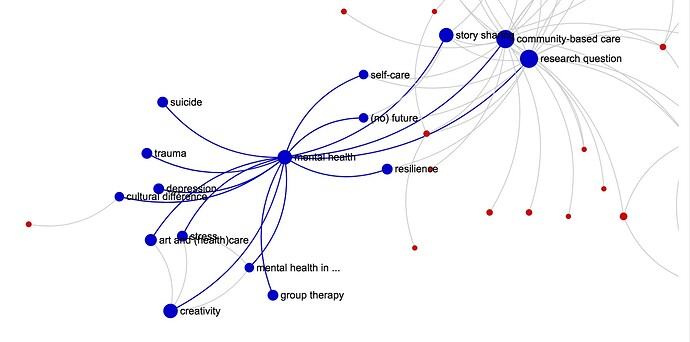

2. Mental Health and Alternative Living

It is perhaps unsurprising with the presence of crisis, precarity, and widespread displacement that mental health issues have come to the fore. Trauma is rife after such experiences, and community members have been trying to find ways to heal themselves mentally as well as physically. Self-care has been a theme, though it has been made clear that going it alone is not a viable option in many circumstances. We need each other to get through, although no one can do it for us. This theme has also shown that sometimes people do need trained professionals---- there is a limit to how much peers can help in certain medical situations. But since holistic healthcare is so important to so many members of the community, trained professionals are only one aspect of mental healthcare. In dealing with trauma especially, connecting people in different places, sharing support and resources, has been crucial. Some people have found group therapy and online support groups useful, while others have found that alternative therapies like meditation and acupuncture help them get through. Gardening can be the key to happiness and healing sometimes, it seems, as can artistic expression!

Part of the reason that Open Carers are so inspiring is their commitment to living life a little differently. Many community members have identified sources of stress that emerge from trying to measure success by someone else’s metric, or taking on expectations at work that far exceed or are completely different from their own desires. Sometimes mental health issues come from sources we can’t fight— depression results from a chemical imbalance in the brain, after all — but some sources are identifiable, and community members have been inventing creative ways of attaining happiness even in the diciest of situations. There is a powerful link, it seems, between creating a life in which someone is able to express themselves creatively and finding mental well-being.

3. Autonomy and Interdependency

Another interesting tension. OpenCarers have a strong desire for autonomy: to be independent from failing systems, to be mobile on their own, to be self-sufficient even when in a liminal space like a refugee camp, to be treated like adults by their governments and public services, to have the power to effect change in their worlds, and so on. Myriad design interventions have addressed mobility issues, allowing people to regain control over their motor functions. Other initiatives have promoted, through skill-sharing and education, the ability of refugees to be self-sufficient despite unfavourable circumstances and temporary living situations. It feels good to be in control of one’s own life, it seems, instead of being at the mercy of institutions that often don’t consult people about what they want and how they care to live.

That being said, communities are interdependent and proud of it. They support each other, share resources, build common spaces, and teach each other new skills. More importantly, they believe this should be the case: communities should be at the heart of health and social care practices, according to OpenCarers. Resilient communities are those that celebrate their interdependency and care for one another, while also allowing each other to flourish in their own individual ways. How to achieve this balance has been an ongoing topic of conversation, since it is not only the collapse of public systems that has troubled Open Carers, but the collapse of informal support systems like extended family units and vibrant communities as well. How do we take care of our communities and strengthen informal ties in the face of increasing collapse of formal systems of care? Or, perhaps the better question is how to improve both, since OpenCarers seem deeply committed to improving both forms of care.

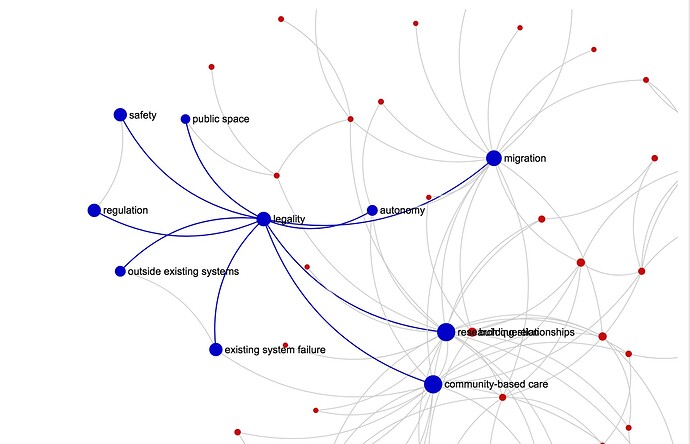

4. Issues of Legality, Regulation, and Safety when working Outside Existing Systems

It is perhaps unsurprising, given the goal of Open Care, that we have heard so many stories about people working at the margins of or outside existing systems. Questions here (when it comes to design interventions especially) rotate around the twin spokes of legality and safety. A community member will ask something along these lines: how can we get around stringent regulations that stop people, usually people without resources like money or the ability to travel, from accessing vital medical interventions? Then, generally, another community member will bring up the issue of safety, especially around clinical trials. These regulations are there for a reason, the community member(s) argue back, to keep people safe from harm. So collectively, the community has generated this more nuanced question: how do we work outside existing systems to give people access to vital technologies of care, while also keeping them safe? The answer seems to lie in self-regulation, in ethics and ethical commitments to good, safe practice. Making rules for spaces is another way in which this happens, as people collectively agree on best practices. Open processes are another way this is managed, with commitments to open notebook science, Open Source and Open Hardware, which maintain transparency and keep everyone honest and accountable.

Finally, working outside existing systems is not always the path chosen by Open Carers. Many community-based care initiatives look to work with policy-makers, or form public-private partnerships, to realise their visions or get the resources they need to deliver them to the people who need them. The desire to rejuvenate urban spaces and revitalise neighbourhoods has been a key space of collaboration between different stakeholders. Change in each case is needed, but the implementation of that change can take different forms depending on the issues at hand.

5. Egalitarian Ideals

Finally, the community as a whole has a strong commitment to egalitarianism, whether it be in the form of cooperative living, transparent and flat governance, distribution of resources, maintaining open processes, fighting against corrupting of corporate greed, or creating alternatives to existing systems of inequality. How to manage equality while also creating systems that work and are effective has been an ongoing topic of conversation, and I imagine will continue to be. How do we make rules for spaces and enact shared governance while being fair to everyone? How do we overcome and/or reform systems that seem hell-bent on perpetuating inequality?

In closing, I am really looking forward to compiling a list of research questions that the community have generated so we can see the key issues at stake in the future of these projects. Stay tuned!

(Question: I had plans to hyperlink this post to all the stories that brought it into being, phrase by phrase, but I ultimately worried that it would be too busy/hard to read. Let me know if that would be helpful! Example: linking <to be self-sufficient even when in a liminal space like a refugee camp> to ‘The Jungle’ post)