In the first time of Future Makers Nepal, we were mostly concerned with assisting the relief work after the earthquake (for obvious reasons …). This is slowly coming to an end, and we wanted to share with you some updates we prepared that summarize what we learned about “grassroots-organized disaster response”, in Nepal and in general.

The first part of what we learned is what actually happened on the ground: who were the disaster response volunteers, how many, what did they do etc… Please find our research updates published below. We will replace this with a link to the proper research paper where we discuss these findings, once UNDP publishes it.

Contributing authors: Meena, Matthias, Natalia.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

-

Situation Overview

-

Methods and Data

-

Findings

4.1. Characteristics of Dialogue and Collaboration Initiatives

4.2. The Rise of New Civil Society in Nepal?

- Case studies: People and Initiatives Making a Difference

5.1 Kathmandu Living Labs: Creating Dialogue and Coordination Spaces

5.2. Milan Rai and Friends: Building Camp Toilets

5.3. Immediate Earthquake Relief for Rural Nepal: Assisting Far-Off Villages

5.4. Community Service of Nepal: Organizing help locally and internationally

- Conclusion and Outlook

6.1. Method Review

6.2. Relevance for Professional Disaster Responders

6.3. Relevance for Disaster Response R&D

Edgeryders’ Future Makers Nepal project was initiated by UNDP Nepal with the aim to research, contact and connect alternative leaders in Nepal using an online platform. As part of this work, we had to carry a “mapping of existing virtual dialogue spaces in Nepal”, the findings of which we detail in this report.

Our start of the work in Nepal coincided with the 25 April 2015 earthquake, after which a huge number of existing web-based dialogue and collaboration spaces was re-purposed for community-driven disaster response, and a similar number of new spaces and initiatives was created for this purpose. These were the most vibrant online communities of alternative leaders in Nepal in the weeks past the earthquake, so we have put particular emphasis on mapping them in the following report.

We find and analyze in detail how after the 25 April earthquake, mostly young volunteers came to the fore, creating their own dialogue and collaboration spaces and on-the-ground initiatives to tackle the effects of the disaster. Effectively, a spontaneous movement of community-driven earthquake response initiatives formed. About half of the initiatives involved formed spontaneously after the earthquake, and a portion of them will transform into new, sustainable dialogue and collaboration spaces in Nepal;s civil society, beyond the current context of earthquake relief. We were lucky to be able to capture the formation of these nascent dialogue and collaboration spaces in this mapping report.

The analysis is devised based on an online database that is created for keeping track of people and organizational initiatives involved in the disaster response activities. It focuses on aspects such as nature of the initiatives, focus of the initiatives, the activity location and the scale of activity. Offline and online dialogue between citizen driven disaster response initiatives and alternative leaders form the basis of analysis in assessing the level of community-engagement. The online dialogue spearheads the understanding of the importance of grass-root efforts in the disaster response. It serves as a unique platform to discuss and learn how people work and coordinate at times of crisis, what motivates them and how they reflect upon their initiatives. This ultimately helps in strengthening and developing a stronger civil society base which can devise constructive solutions to problems, develop sustainable collaboration between people and relief organizations and prepare Nepal for unforeseen circumstances in the future.

This report provides an overview of some of the community driven responses to the recent crisis in Nepal. For the purpose of this study we define ‘community-driven responses to disaster’ as any disaster-related response activities that are not initiated by professionals officially designated to do relief work (including security forces, governmental structures, UN system, INGOs and NGOs among others). The Future Makers Nepal team did a preliminary mapping of 121 volunteer driven disaster responses that emerged in Nepal in a span of a month following the earthquake. The following findings are a result of a two-week-long analysis of the data available online, combined with conclusions derived from informal meetings with people engaged in the relief efforts.

A 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck Nepal on the 25 April 2015 and was followed by numerous aftershocks left thousands dead, injured and properties worth millions ravaged. The earthquake also destroyed some of the most important cultural heritage of Nepal. The government report shows that over 35 of the 75 districts are affected in the Central and Western Regions including the Kathmandu Valley and 14 of these districts were identified as ‘priority affected districts’ depending upon the severity of the damage. Reportedly, Gorkha, Dhading, Sindhupalchok, Rasuwa, Nuwakot, Bhaktapur, Kathmandu, Lalitpur are the districts that are highly affected by the earthquake. As of 31 May, the Home Ministry reported a total of 8,693 deaths, 22,221 people injured and over 505,000 homes fully destroyed and another 275,000 partially destroyed.[2] The earthquake also ravaged more than 70 percent of the cultural heritages of Nepal listed in the UNESCO heritage site.[3] In addition, the official estimates put forth by the World Health Organisation show that 8.1 million people out of a population of 28 million have been affected by the earthquake, amongst which 1.7 million are children.

Nepal’s Ministry of Education estimates that 23,644 classrooms have been damaged or destroyed, and an additional 10,922 classrooms have received minor damages in the priority affected districts alone.[4] For a country like Nepal, prior to the earthquake tackling an alarming number of issues pertaining to political tensions, slow economic progress, poverty, unemployment, energy crunch, among others, the task of rebuilding now turns out to be a herculean one. The country now faces another major setback in its development trajectory and what is needed at this hour of crisis is a good leadership and above all the collective strength of common people.

However, the way the young Nepalese took up the task of reaching out to the victims speaks a lot about the concern they have shown towards their society, thus projecting a sense of natural ‘community resilience’. While majority of the people remained outside houses for numerous days, there were these certain groups of individuals and organizations that took charge. They worked day and night to give to the living by voluntarily rendering whatever support they could. Some crowd-sourced funds for immediate relief or transported relief materials to the affected areas, while others took up the task of setting up platforms for disseminating crucial information outside the traditional modes of communication, and a significant number of youths collaborated with government authorities. The preliminary mapping for this report recorded 121 voluntary disaster response initiatives out of probably more than 250 voluntary disaster response initiatives that have published anything online, and many more who did not. It will be years before Nepal recovers from this catastrophe, however, the country is fortunate to have motivated youths, bounded with an unprecedented sense of collective responsibility, community spirit and social consciousness to rebuild Nepal.

The data pertaining to community-driven initiatives after the 25th of April earthquake and subsequent aftershocks are gathered through online and offline sampling. Most of the data was extracted manually from publicly available, unstructured Internet content published by the respective initiatives. This method was fast and efficient to stay within project constraints, and lead to relatively complete results. The alternative of inviting initiatives to a survey would have lead to somewhat more exact data, but would have been slower, taking time away from actual relief efforts and thus only a low turnover could have been be expected.

An online database of individuals and initiatives that were involved in various types of post-earthquake disaster response endeavours is devised to collect certain type of information the research focuses on. Based upon this dataset, initiatives are selected and featured in the Future Makers Nepal online platform through interviews and are invited to take part in the online dialogue that this virtual community supports. The method also uses case studies as a basis of qualitative analysis in examining the initiatives, their nature, scope and challenges. These case studies are further taken as a basis for formulating an analysis for the post- earthquake disaster response carried out by people and institutions.

At this stage, the database contains 121 records of community-driven disaster response initiatives. Initiatives are further analyzed by devising categories to measure the intensity and diversity of their earthquake relief responses and recording this information in the database.

The first criterion concerns the activities carried out by the community-driven initiatives. Categories for this are largely aligned with the UN cluster system for comparability. However, sub-categories for activities have been added where required, allowing a more detailed analysis of interesting aspects not covered by a UN cluster system categorization. For instance, the information management category is further divided into crisis mapping and volunteer placement, and the relief supplies category is further segregated by type of supplies.

The location of the initiatives has been analyzed on a district level. Where more specific information was not publicly available, initiatives that operate location-independent (e.g. fundraising campaigns) have been assigned the 14 government designated priority affected districts.[5]

The initiatives and projects are also analyzed based upon their nature, that is to say if they have emerged spontaneously following the 25th of April earthquake or if they derived from the pre-existing organization structures that diverted their focus after the earthquake.

Finally, the scale of the initiatives has been recorded, using categories that could be easily inferred from publicly available information and are meant to gauge the internal coordination complexity of the initiatives; namely, if the initiative was an individual effort, or a work done by one team, multiple teams, or multiple teams using multiple base locations.

4.1. Characteristics of Dialogue and Collaboration Initiatives

Activities

Each community-driven earthquake response initiative was sorted into all types of response activity categories. The current dataset shows the following significant clusters of activity:

- Supplies – With 58 of 121 mapped initiatives (48% approx.) covering this, the immediate supply of relief materials was the most common choice of activity. Initiatives further differed by the selection of relief materials they provided (shelter supplies like tarps or tents, food supplies, health supplies incl. hygiene and medicinal articles, educational materials, housing reconstruction materials, and ‘other supplies’; see image 1 for a breakdown). Initiatives were only assigned a ‘supplies’ category if they simply provide materials to people in need, without using them further on location (like for example for building shelters).

- Information management – About 41% of initiatives covered information management, making this the second most commonly chosen activity. It is interesting to note that there was a significant upsurge of an online community dedicated in post conflict disaster management. It was assigned for any relief-associated activity related to relief coordination, assessment, data collection and information sharing beyond the immediate needs of the own initiative. Crisis mapping (creating online and offline maps) and volunteer placement (matching volunteers with opportunities) were separated out into sub-categories as there were many individuals and institutions that focused their disaster response activities towards these. Furthermore, many (62%) of the information management endeavors were initiated by persons and organisations that came up spontaneously after the earthquake. Various people and initiatives also created an online record with contact numbers and hotlines of relevant government authorities, hospitals, medical clinics, blood donations and ambulance services.

- Fundraising – Fundraising turned out to be another mostly opted disaster response initiative which was voluntarily carried out by individuals and organisations. The finding shows 17% of initiatives (21 out of 121) taking up the task of crowdfunding campaigns for own or others’ initiatives.. They are split into almost equal numbers of pre-existing and spontaneous initiatives (11 and 10 records, respectively).

Beyond the these major activities above, community-driven initiatives focused on various other areas. The categories used for these activities are:

- Education – building schools, temporary and transitory learning centers in camps and villages, educating teachers about handling PTSD in children, among others. Taken up by 10% of initiatives.

- Health – including medical treatments, nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene. 8.2% uptake.

- Reconstruction – building permanent housing and / or teaching how to do it. 10.7% uptake.

- Shelter – building temporary housing and / or teaching how to do it. 10% uptake.

- Tech-support – developing and installing photovoltaics equipment, building livability assessment, and other professional services. 10% uptake.

- Support to women and children – an additional tag for activities with a special concern for women and children (e.g. distributing female sanitation packs, care packages for pregnant and breastfeeding women). 5.8% uptake

Image 1: Relative frequency of activities carried out by community-driven disaster response initiatives.[6]

Service Locations

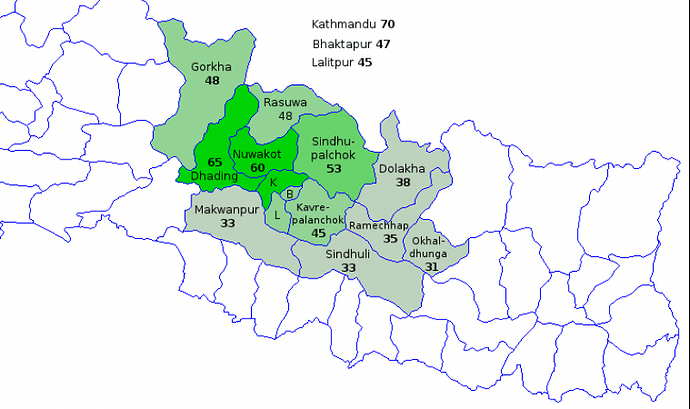

The community-driven initiatives by individuals and pre-existing organisations were distributed throughout the locations that were severely affected by the earthquake. With 70 records (58 percent) of initiatives as per the database, Kathmandu turned out to be the center location for most of the disaster response activities, followed by Dhading (65 records), Nuwakot (60 records), Sindhupalchok (53 records), Rasuwa (48 records) and Gorkha (48 records). These can be considered the focus areas of the volunteer initiatives. Given that many number of initiatives rendering volunteer service are centered in Kathmandu and other periphery areas, we can easily infer that the geographical terrain and accessibility still stands as a determining factor for any kind of post- disaster relief operations. Other priority affected districts like Sindhuli, Ramechhap, Dolakha, Makwanpur and Okhaldhunga, and also some less affected districts like Pokhara, Lamjung, Solukhumbu also saw several activities of volunteer initiatives carried out in the earthquake affected areas though at slightly lesser scale. Okhaldhunga saw the least number of community-driven disaster response initiatives (26 percent of initiatives covered it). This might point to difficult terrain in this hilly district, the distance from Kathmandu as a hub location for initiatives, and / or a perceived low level of damages.

Image 2: Deployment locations of community-driven disaster response initiatives at district level among the 14 priority affected districts. (Totalling 651 locations by 121 initiatives.)

Nature of Initiatives

The community-driven responses to the earthquake were carried by individuals / organisations that emerged spontaneously in the wake of the crisis (58 records) and by pre-existing organizations shifting their focus to disaster response (63 records). The emergence of significant number of new engaged individuals and initiatives in the wake of crisis paints a positive picture of community resilience and civil society activity. For example, 30 of the 58 spontaneously emerged disaster response initiatives directed their activity towards supplying immediate relief materials and 31 towards information management (incl. crisis mapping and volunteer placement; see image 3). There were also significant number of spontaneous initiatives that worked in the area of shelter (15 records), health (14 records) and fundraising (10 records).

Image 3: Absolute uptake of activities (number of initiatives involved out of 121 in total; split by nature of initiative)

Scale of Initiatives

With 56% of initiatives carried out by one team, working in small groups was the major mode how community-driven disaster response was organized. All larger-scale initiatives combined accounted for 36%. Generally, smaller-scale organizations were more frequent than larger-scale ones (compare image 4). This organization size distribution is to a degree universal – it is also found, for example, for company sizes.[7] For the surveyed disaster response initiatives, there is one major exception from this rule: single-person initiatives as the smallest organization forms account for just 8%, which is much less than the next larger scale category has. This means that team work clearly stands as the spirit and mode of function of community-driven disaster response.

Image 4: Scale of Community-Driven Disaster Response Initiatives

4.2. The Rise of New Civil Society in Nepal?

When it might have been thought that the country which was already in tatters due to its decade long Maoist conflict and the subsequent political turmoils, reeling problem of corruption and underdevelopment will further divulge in a situation of hopelessness following the recent natural disaster, it was fascinating to see the outpouring of citizen engagement and the rise of new community organisations. What made this rise of ‘public sphere’ more interesting is the nature of their emergence, that is to say the spontaneity of their rise in the wake of crisis. The findings show that 52% of the mapped organisations that were engaged in disaster response activities were the ones that already existed while 48% of initiatives emerged spontaneously after the crisis. There seems to be a significant number of voluntarily driven citizen engagement endeavors with their focus on supplying immediate relief materials and more importantly, on information management. This is heading towards an emergence of tech savvy, philanthropic new civic leadership. As per the findings, about half (29 of 58) of newly emerged initiatives tasked themselves with general information management (coordination and need assessment), and several more took on crisis mapping or volunteer placement, in most cases additionally. Based upon these findings we can see a rise of new civil society in Nepal: Besides the conventional civil society activities, largely related to politicised mass mobilisations, there is now a new model of self-directed citizen engagement. The next challenge that lies ahead is to enable this ‘new public sphere’ to effect lasting social change: rebuilding communities, rehabilitating victims and most importantly, reestablishing enduring trust in government by coordinating effectively with it.

5. Case studies: People and Initiatives Making a Difference

Based upon the online dialogue that takes place on our edgeryders.eu platform, some of the surveyed initiatives are presented here in more depth as typical examples for different varieties of initiatives, differing by activities (here information management, health, fundraising and providing immediate relief supplies) and scale (here one or multiple teams). Some but not all of the initiatives presented here emerged spontaneously after the disaster, so they also differ in history.

5.1 Kathmandu Living Labs: Creating Dialogue and Coordination Spaces

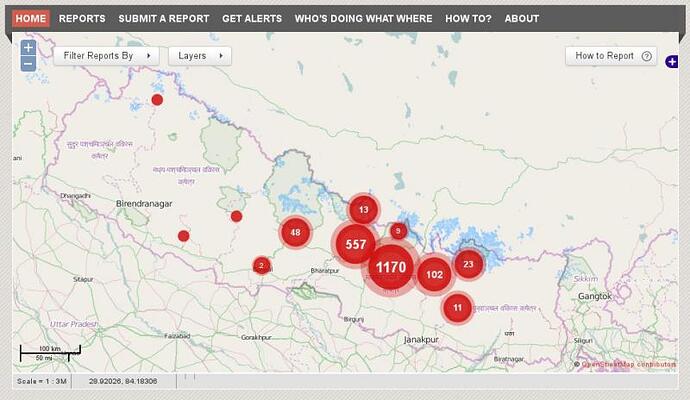

Kathmandu Living Labs[8] is a tech group that existed before the earthquake. It has been using mobile and internet based technology in order to enhance urban resilience and civil engagement in Nepal and it has been doing exactly this after the earthquake. It created an online, as well as offline, map to assist earthquake relief workers and volunteers by mapping the affected villages, thus helping relief operations to reach the affected areas. Quakemap[9] is an initiative led by Kathmandu Living Labs. It was set up as an immediate response to coordinate the relief efforts of volunteers and volunteer-driven initiatives. They provide a wide range of information, including identification of affected districts, the needs of affected people, and acting as a bridge between the relief providers and the relief seekers.

Image 5: Main screen of quakemap.org by Kathmandu Living Labs[10]

5.2. Milan Rai and Friends: Building Camp Toilets

An enthusiastic young adult, Milan Rai and his team, built more than 140 temporary toilets in camps in Kathmandu and other affected areas. Confused initially as to how to react to such a grave crisis, Rai took up the lead by urging people to go to a safe place and to ask others to do the same. For Rai, there was no sitting back and panicking. He cycled all the way to the hospital at 3 am to help the needy. After surveying around Kathmandu where people have camped, Rai found out that there were no toilets at all. Worse, he found girls complaining that they had to wait for the night to relieve themselves. Milan along with some of his friends therefore thought of fulfilling their part of the relief work by setting up temporary toilets. For them, setting up toilets was not merely about ensuring health, hygiene and sanitation, it was also related to self-esteem and dignity of the people. They built the toilets with tarp and bamboo, which required less time to install and could be easily transported and fitted. With some voluntary support by army members, they were able to build 47 toilets during their first day. Milan and his like-minded team are on a “helping spree”: after setting up temporary toilets, they are now promoting growing vegetables and planting seeds. As they grow mature with their disaster response endeavours they have been able to better organise their work and ensure more sustainable solutions.[11]

Image 6: Temporary Toilet Building by Milan Rai and Friends

|

“We saw a lot of people in the public spaces where they were camping but there were no toilets. Especially the girls complained that they had to wait for the night in order to relieve themselves. We realized that if we were unable to tackle this issue then this would be the source of epidemic outbreak”. – Milan Rai |

5.3. Immediate Earthquake Relief for Rural Nepal: Assisting Far-Off Villages

Immediate Earthquake Relief for Rural Nepal is a group of friends from diverse backgrounds who came together spontaneously to carry out relief work in earthquake affected rural parts of Nepal. They started their relief initiative by reaching out to a village in Nuwakot through a personal contact and were largely sought-after by villagers and asked for help. While they received accolade, they utilized the trust placed into them to raise funds and relief materials to be distributed to the affected people. So far, this group has assisted people with relief materials worth around $23,000, covering 44 villages in nine districts. They headed an organised disaster response endeavor, coordinating with government authorities to locate the vulnerable areas and people. Their activities included need assessment, ensuring accountability and looking into the nooks and crannies that usually go unnoticed. One important lesson this group teaches is that of community resilience – the ability to anticipate risk, limit impact and bounce back quickly in the face of turbulent changes.[12]

|

“We were out of the house three days after the earthquake. I think it was pure emotion initially. We could either have stayed quiet or we could have worked. There is an emotional drive after you see people in need. You cannot not do something.” – Rakesh Shahi |

5.4. Community Service of Nepal: Organizing help locally and internationally

After the 25 April earthquake, the greatest challenge that stood ahead of Madhav Bhandari and his team was to provide relief materials to people affected by the earthquake in a widely scattered village in Sindhupalchok. With almost 6000 people homeless in only three inaccessible villages of the districts, Community Service of Nepal – a registered non-profit community organization that does charity and humanitarian work – took up the initiative to distribute tents to the homeless people. Within a couple of days after the quake, they were able to locate a source that donated them with 1000 tents to be delivered to the affected people.

Having distributed tents and other relief materials to those in need, the next challenge that lies ahead of the organization is to provide the homeless with corrugated metal sheets which are in high demand. Another task for this humanitarian initiative is to seek support from ‘cluster of contacts’ for different types of aid designed by the United Nations and the government of Nepal in carrying forth the disaster response to materialise their goal of reaching larger group of affected people through the distribution of food, shelter and medicines. They have been doing every possible thing, from connecting into the official network of aid, to finding possible ways to make it easy to drop off relief materials in areas inaccessible by road to exploring ways, to address the demands and concerns of the affected to make sure that thousands of homeless people have a place to stay.[13]

|

“The corrugated iron is much more expensive than tents, but the people know what they need much better than we do because they are the ones who need to live in their own situation. We need to change all of our fund-raising appeals to corrugated iron, and we need to find a cheap source of the iron sheets.” – Lisa Bates |

The chosen method was reasonably effective and efficient to detect key characteristics of the community-driven disaster response movement after the earthquake in Nepal, including activities, location, group nature and scale. It also worked well to inform research questions for follow-up work. However, the nature of the data and data collection prevented us to work out some of the more subtle properties of the movement. Specifically, the limitations arose from:

- Inexact data. Since data was collected from publicly available sources, and these publications were made in an unstructured and ad-hoc way in a post-disaster scenario, data would be missing in some cases and be inexact in others. This was countered by choosing a high granularity level (location by district instead of VDC, scale in 5 levels instead of number of collaborators etc.). But consequentially, analysis was limited to this granularity level as well. For example, it is not possible to give an estimate of the amount of relief work done by the community-driven initiatives, or to detect if these initiatives missed out to cover some unserved areas, without conducting a more detailed and time consuming research.

- Missing public data. Several interesting pieces of information cannot be reliably determined from public records. For example, it would have been interesting to know the proportions of how many Nepali people and respectively foreigners founded, lead and contributed to initiatives, but this is only possible to find when interviewing initiatives, so hardly in a comprehensive way for all of them

- Fuzzy data. Boundaries between initiatives were fuzzy in several cases (e.g. coordinated multi-team initiatives like Yellow House), and the categorization was not able to capture this properly. The same problem applies to numerous activities: they were meant to present the core concerns of initiatives, but some initiatives did ‘a bit of everything’, making them hard to analyze.

- Requiring online information. Relying on analyzing first and secondary source online publications meant that the method could only find initiatives about which something was published online. Due to the ubiquity of Facebook as a coordination tool among initiatives, this includes virtually all initiatives operating from cities. Therefore, the method did not find independent relief operations at village level, which are managed by local resources and manpower only and, without the privilege of online coverage, have high chances of going unnoticed. With this method, disaster response volunteers in villages were covered only insofar they collaborated with initiatives reaching out to them from the cities.

For a more complete picture of the significance of community-driven earthquake response, potential further research should answer the following question: How much did the different types of responders contribute to total relief and reconstruction work after the earthquake? This relates to self-help, neighborly help, community-driven disaster response at village level, community-driven disaster response at regional and national level, government and security forces, and disaster response by the international community of donors and response professionals (incl. UN system). This question cannot be answered by mapping using public information as in this study, but would require a field study in randomly chosen settlements, followed by statistical estimation.

The second major limitation is that of quantitatively analyzing key facts about initiatives does not grant insights into their inner working models, processes and challenges. Follow-up research should employ qualitative methods like ethnography to acquire these insights.

6.2. Relevance for Professional Disaster Responders

The findings relating to community driven response to the earthquake in Nepal can be a basis for professional disaster responders to facilitate broad based local preparedness for long-term emergency response and other local efforts. By devising frameworks and conducting trainings for information management, crisis mapping, assessing local power structures, needs evaluation, conflict-resolution skills, supplies management methods, and community-profile development, these professional disaster responders would ultimately contribute by informing the citizens that their involvement is essential to local development well beyond times of disaster. This will in due course of time ultimately foster well-planned and effective reconstruction activities. Likewise, more similar grassroot mobilisation can be planned for, and responded to in the aftermath of the disaster. Furthermore, processes such as bringing together diverse local groups, formation of local groups for planning, establishing long term vision and goal setting for disaster preparedness / recovery and recruitment of experienced local citizens can to lead the reconstruction. They could further also contribute by establishing an alliance between local groups that have been affected from the same areas and set a stage for more effective resource and responsibility sharing during times of crisis. Such alliance can therefore serve as a liaison between local grassroot efforts and more formal structures. Professional disaster responders could ultimately fill in the gaps by rendering support in areas which were not covered by the voluntary institution primarily due to inadequate professional expertise. For instance by providing staff for medical emergencies and treatments.

6.3. Relevance for Disaster Response R&D

Disaster response is under increasing scrutiny to work efficiently, transparently and accountable. Thus, it is worth keeping an eye on recent developments in technology, social changes, and grassroots innovations.

This study identifies and analyzes community-driven disaster response as one of the grassroots innovations that can help to improve current disaster response mechanisms. In its movement-scale form observed in Nepal, community-driven disaster response can be considered an application of Internet-enabled peer-to-peer communication, collaboration and funding mechanisms – a latest addition to recent disruptive innovations like collaborative economy platforms, knowledge sharing platforms and digital collaboration platforms.[14] Obviously, such a development was only possible after widespread Internet uptake, now a given in urban Nepal.

Designing a tool that further empowers community-driven disaster response and enables efficient coordination and collaboration with professional disaster responders is a task beyond the scope of this project. Relevant research questions for further work include:

- Have community-driven disaster response initiatives been truly successful in matching needs to provided supplies and help? What factors influence their level of success in this?

- How can the spirit of voluntarism and generosity be sustained when dealing with other challenges in Nepal, not just during a few weeks of volunteer disaster response work?

- Can the new, spontaneously emerged community-driven initiatives transform into permanent and established actors in civil society? Is that desirable?

- In what ways can community-driven initiatives contribute to reconstruction?

For such future work, the database and analysis of initiatives provided here is a viable basis. Informed by it and extrapolating from current technological developments, here is an idea-stage list of possible design aspects of such a tool:

- Preparing appropriate knowledge tools. A major challenge for community-driven disaster response is that they have to build up their knowledge base and coordination toolset while doing the relief work, which means, under severe time constraints and with incomplete information.. Professional disaster preparedness organizations may want to provide support for compiling knowledge into compact ‘field manuals’ beforehand, esp. including best practices for coordination that were observed among community-driven responses to past disasters.

- Humanitarian Data Information System (HDIS). The public Humanitarian Response platform[15] is a tool provided by UN OCHA to coordinate humanitarian response operations. It provides up-to-date situation reports, event notifications and key documents for download, and is complemented with the recently launched Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) platform.[16] HDX is a platform for visualizing and downloading datasets, based on the open source software application CKAN.[17] An information system is a natural extension of this setup. In contrast to downloadable reports, an information system is an online database that provides real-time authoritative information, preventing data redundancy, inconsistency and duplication. This makes it a useful coordination tool also for community-driven disaster response initiatives, which in contrast to professional disaster responders do not have their own internal coordination tools and mechanisms and currently rely on ad-hoc solutions.

- Phone-based coordination and assessment tool. Different from professional disaster responders, members of community-driven initiatives in Nepal mostly use the phone and unstructured Facebook forums for coordination. They have neither the training, Internet connectivity, patience or formal obligation to coordinate via structured data input into software applications. This limits their own efficiency, and excludes most coordination with professional disaster response organizations (esp. via the UN clusters). To accommodate the contributions of community-driven responses, a national single-number hotline could work. Information managers in a call center would both take and make phone calls to provide and collect information, and would be trained to relay all this to the information system discussed above.

[1] We thankfully acknowledge funding of this research by UNDP Nepal, via contract UNDP/INST/012/2015.

[2] Government of Nepal Disaster Risk Reduction Portal, http://www.drrportal.gov.np/, accessed 31 May 2015.

[3] Rajneesh Bhandari, Jonah M. Kesse: Rescuing Nepal’s Relics, 20 May 2015, nytimes.com/video/id/100000003695666/video.html, accessed 31 May 2015

[4] Government of Nepal: Ministry of Education: School Building Preliminary Damage Assessment, version of 22 May 2015, moe.gov.np/allcontent/Detail/374, accessed 31 May 2015

[5] This seems a good approximation, since only very few location-bound initiatives operate in districts beyond the 14 priority affected ones: Gorkha, Dhading, Nuwakot, Rasuwa, Sindhupalchok, Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Lalitpur, Makwanpur, Dolakha, Kavrepalanchok, Sindhuli, Ramechhap, Okhaldhunga. Source: tinyurl.com/nepal-affected-districts

[6] Each initiative could carry out multiple types of activities. Thus, values differ from activity uptake / coverage percentage numbers mentioned in the text.

[7] Compare for example: U.S. Census Bureau: Statistics about Business Size (including Small Business) – Employment Size of Firms, census.gov/econ/smallbus.html#EmpSize, accessed 2015-06-08

[10] Shows map imagery from OpenStreetMap, © OpenStreetMap contributors. OpenStreetMap is open data, licensed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL) by the OpenStreetMap Foundation (OSMF). See http://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright for details.

[11] For more details see: https://edgeryders.eu/node/4744

[12] For more details see: https://edgeryders.eu/node/4704

[13] For more details see: https://edgeryders.eu/node/4632

[14] For a database of over 9,000 different collaboration and sharing platforms, see Meshing.it, http://meshing.it/categories.

[17] See http://ckan.org/