A year ago I was invited to do a talk at a creative industries event called Improving Reality. In it I presented two areas where I believe culture can play an important role. The first is in helping us to succeed in undermining the rise of authoritarian movements in our societies. This in turn is depends on the second area: helping use to bridge the gaps between need for making a living and need for meaning. I believe that successfully addressing both is a key to getting us out of this mess we are in.

Poverty of imagination in combination with lack of access to working models for how people can sustain themselves outside the full time long term employment paradigm creates a vacuum. A vaccum which authoritarian leaders can fill with whatever empty promises they like. Because people who are scared about their future livelihoods and social protection are very easy to manipulate into making really bad decisions for others…and themselves.

It is not just the religion-flavoured authoritarianism we should be worried about. It also seems to drive conservatism and nostalgic longing for a mythical past where everything was better and more predictable. Daniel Vaarik’s story of United Estonia is a frightening indicator of how quickly things can spin out of control in modern liberal democracies if this vacuum is left unchecked:

“OMG, what is this video?” I can’t even begin to explain. You’ll have to read Daniel’s mind boggling story about United Estonia.

But what does all of this have to do with terrorism?

Because climate change. And export of military technology. And contributing towards financing Daesh and various dictatorships by running our economy on non renewable energy sources. Because accepting a culture where we are callous towards the suffering of others is accepting a society where our own lives have little value.

You cannot export despair and destruction without having to pay the price sooner or later. If we don’t find new ways of sustaining ourselves that don’t contribute towards people having to flee their countries in the first place, then we will never get out of the international cycle of stupidity. But change is hard. This is established by now. What is not so obvious is how culture can be channelled towards helping fix the problems. I’d like to propose two statements as a starting point for a conversation:

- Through culture we can shape new understandings of value, meaning, and work. Which in turn can improve our ability to use innovation against systemic crises.

- Through culture we can also influence how politics is done, where and by whom. Which in turn can build the political and institutional demand for innovation against systemic crises.

Let me try to unpack this.....

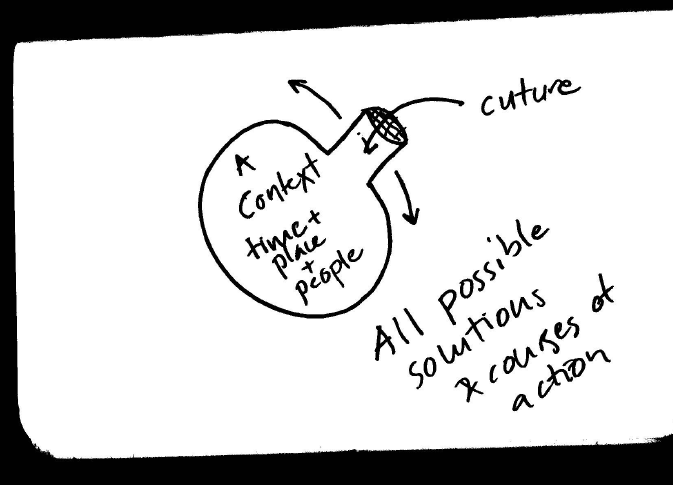

Change often begins at the edges of what is deemed acceptable - culturally, economically and legally

<img alt="" src="http://designobserver.com/media/images/37567-chart_525.jpg" style="width: 525px; height: 388px;">

Image source: the German Advisory Council on Climate Change (WGBU)

Even though this initial input is needed by the mainstream in order to adapt, our societies seem to be moving towards increasingly authoritarian cultures which react aggressively towards any kind of departure from the norm. This aversion to new alternatives seems to get worse when people are scared about their personal socioeconomic security. And it makes sense. In our contemporary lives everything is defined in relation to work.

Culture guides our behaviour. You need to have the cultural space for something to exist in order for us to be able to recognise, interact with, and shape our values around it. If you want to very tangible example of this, have a look into the relationship between futurism and the rise of facism in Italy. This is why I believe our ability to use innovation against systemic crises is limited by our ability to shape new cultural understandings of value, meaning, and work. If you adopt this view, one conclusion is that responding to global systemic crises boils down to coming up with new ways of bridging the growing gap between the need to make a living and the need to create meaning.

Our ability to use innovation to resolve systemic crises is limited by our ability to influence how politics is done, where and by whom.

In this Vice interview with Kristina Persson, the current Swedish minister of Nordic cooperation and Future Issues, it is clear that she is interpreting her ministerial role as one that strives to change the culture within which political and institutional decision makers act. This is not a coincidence. Three years ago, Kristina commissioned a project from Edgeryders: an open conversation around issues of employment, migration and political participation grounded in first hand accounts of self selected participants living in different parts of the Baltic Sea region. We then had scholars point to the ruptures between how insitutional culture understood and approached challenges…and the lived reality of those whom they are meant to serve. My summary of Edgeryders contributions is available here. When we did public talks about this, our conclusions seemed to resonate with people regardless of age, profession etc. More recently I heard jesper Christiansen who heads Mindlab’s research work describe something similar- that their role was to drive a change of instutitonal culture. Culture can be seen as a key enabler in shaping the political and institutional demand for alternative solutions..

Culture is a powerful carrier signal for deeper changes in a community.

Video of the announcement of the city of Matera as winner of European Capital of Culture 2019.

It is also cheap and fast in comparison to other kinds of intervention. So it makes sense to better understand how we can work effectively with and through culture to unfail our approach towards dealing with the rise of authoritarianism and violent extremism. A first step is to push for an interpretation of the production of culture as a participatory process.

Once you are on board with the thinking- how do you translate it into effective investments of time and money?

This requires widespread knowledge of administrative plumbing and workflows that allow for new ways of doing things. Brickstarter produced this report in which they describe really well why we need to shed light on what they call the “dark matter” around doing anything new if it involves dealing with large organisations (in their case public administrations). Meaning: we need to learn from previous efforts to hack administrative processes and introduce new ways of working. Do you know of individuals who can share their experiences of having to come up with new administrative workarounds to implement relevant polices?

Wait but what happens in the long run? Oh oh... the stewardship problem

In order for us to be able to really tackle major challenges that require long term work we need to figure out how to improve the odds of creative initiatives being around long enough for us to see the results. Clearly, an initiative is a lot more resilient if it has a community behind it. Even though we know that networked communities are capable of tacking large and ambitious tasks like providing care services, or caring for public assets there is a huge market failure when it comes to stewardship:

Even when it comes to culture in the form of immaterial assets, there are many examples of how quickly achievements can be unravelled without provisions being made for stewardship. Exhibit At being what happened in Matera in the aftermath of the elections. I’ll leave it to @ilariadauria to explain this if anyone is interested ![]()

One of the key obstacles to sustainability of creative initiatives, and the individuals who drive them, is lack of access to permanently affordable spaces for living and working in urban environments. If we could come up with credible models for securing and stewarding material assets then that can unlock a lot of creative resources and investment. So we ought to bring together people who have hands on experience from relevant initiatives: both failed and successful ones.