Maybe it’s my own wishful thinking, but I sense a stirring in the Force around economic theory. Since my undergraduate years, I have been unhappy with the dominance of neoclassical economics, and have been tracking contributions that stand outside of it. In the 1990s-2000s many have come from non-economists: biologists, complexity scientists, economic anthropologists. In the 2010s things have started to change. This change might be encouraged by the ticking Doomsday Clock of the climate-and-environmental crisis: policies inspired by the neoclassical model (like environmental economics in the 1990s, that I used to believe in myself) have failed to slow it down, and some scholars are looking elsewhere for answers.

In this context, I would like to make a quick note here for three recent contributions, two academic and one from the policy world. Maybe something to inspire your next cli-fi bestseller?

1. Satisfying human needs with sustainable energy use is doable, but you need direct provision of key services, and forego economic growth

This is a fantastic paper, called Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use: An international analysis of social provisioning, by Vogel et el., 2021. The idea is this: as we know, humans need to consume energy to satisfy their needs. We also know that the relationship between energy consumption and needs satisfaction is one of saturation: at low levels of energy consumption, an additional amount of energy satisfies needs a lot better. As satisfaction increases, further inputs of energy are less and less effective, until they become zero. The authors claim that how economies supply energy matters. They call this “how” provisioning factors (PFs): access to electricity, health care coverage, sanitation, equality, economic growth etc.

PFs “shift the saturation curve” relating needs satisfaction to energy consumption. Some shift it up: you need less energy to achieve the same level of needs satisfaction. These PFs contribute to sustainability. Others shift it down: you need more energy to achieve the same level of needs satisfaction. These PFs undermine sustainability. Finally, some have no significant statistical effect.

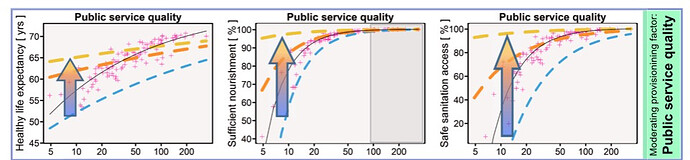

In the next figure, you see the effect of the level of one of the PFs, public service quality, on the relationship between energy consumption (X axis) and three need satisfaction variables (Y axes). The blue curve represents that relationship when the PF in question is at the minimum level among the 106 countries; the orange, when it is at the median level; the yellow, when it is at the maximum level. The impact is huge, especially at low levels of energy consumption (towards the left of the graphs) – which is where you want it.

The results are estimated on a cross-section of 106 countries in 2012. The authors use statistics very cleverly: if statistics is your thing, they compute a model where human need satisfaction is the dependent variable. The independent variable are energy consumption, each PF separately, and the interaction term between energy consumption and PF. This latter captures synergic effects. They then estimate the marginal effects of PFs.

Results are:

- Eight of the twelve PFs examined have unambiguously beneficial effects (positive for all six needs satisfaction variables). These are: public service quality, public health coverage, trade and trasport infrastructure, electricity access, access to clean fuels, urban population, income equality, democratic quality.

- Two have unambiguously negative effects. These are: what they call extractivism (roughly the share of GDP derived from natural resource extraction), and economic growth.

- Two have non-significant effects. These are: foreign direct investment and trade penetration (roughly the share of GDP derived from foreign trade).

- Satisfaction of human needs as defined in the paper is possible within the “sustainable energy consumption limit” of 27 GigaJoules per capita, if beneficial configuration of provisioning factors are observed.

- “these findings imply that economic growth beyond moderate levels of affluence is socio-ecologically detrimental.”

- “The positive association we find between income equality and socio-ecological performance supports claims that improving income equality is compatible with rapid climate mitigation.”

2. GDP growth does not imply an improvement in the average citizen’s economic perspective

This point is made by The Two Growth Rates of the Economy, by Adamou et. al. (2020). One of the co-authors is Ole Peters, and it builds on the idea of ergodicity economics, that we already discussed here. This might seem counterintuitive, but the paper makes a straightforward mathematical argument for it. In practice, according to the authors, GDP growth per capita is an average of the growth if the incomes of each person in the economy, but it is weighted by the person’s income. That makes it a “plutocratic measure of growth”, because it puts more weight on the growth of the income of the rich. Elsewhere, Jason Hickel has argued that GDP growth stands not for the health of the economy, but for the health of capitalism itself.

A different growth rate results when you compute unweighted average of the growth rates of all individuals in the economy. This second growth rate is always smaller than the first. It can be equal in the extreme case in which the income of all individuals grows at the exact same rate. This second growth rate is a “democratic measure of growth”. The authors then go on to study the gap between the two in the USA and in France. The gap is significant in both country, and growing in the USA (but not in France).

It follows that you can very well grow GDP while making the average person in the economy significantly worse off.

3. Growth without economic growth

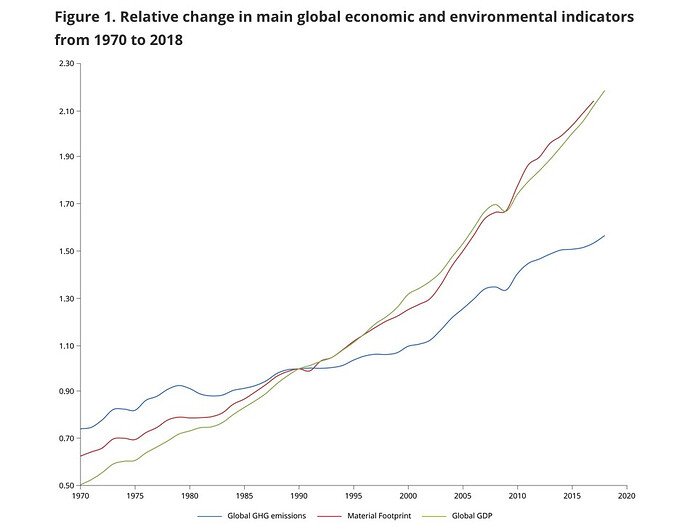

The European Environmental Agency published a policy briefing called Growth without economic growth. Its authors side themselves with Jason Hickel and most ecological economists in pointing out that the “Green Growth” model championed by international organizations is likely incompatible with containing global warming within the 2° C limit. In theory you could decouple GDP from materials consumption, but in practice this is not working out.

In theory you could make the economy circular*, but in practice a lot of the materials consumption is non-recyclable, because it goes either into energy provision (and degrades) or gets fixed into the building stock. In the EU, only 12% of our materials consumption gets recycled.

Conclusion:

Growth is culturally, politically and institutionally ingrained. Change requires us to address these barriers democratically. The various communities that live simply offer inspiration for social innovation.