Governments and tech companies are reaching for tech-based tools to help defeat the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of the solutions under discussion imply restrictions to civil liberties and human rights, like the right to privacy (here is Edward Snowden weighing in).

This is creating uneasiness in the communities I am a part of – a disturbance in the Force, if you are a Star Wars fan. People worry, but no one is sure what an appropriate diagnosis and response to the situation would be. Is the situation “problematic” or “dystopian”? Can we do anything about it, besides worrying?

You see, there are two kinds of problem. For the first kind, the more knowledge people gain about the problem, the less they worry. For the second kind, the more knowledge they gain, the more they worry. Nuclear power production belongs to the first kind; climate change belongs to the second one. Is government-corporate use of tech surveillance more like nuclear power, or is it more like climate change?

The puzzle is complex, and no single person seems to have all the pieces. But that does not scare me: I am part of Edgeryders, and In Collective Intelligence We Trust. So we organized a community listening point to touch base with each other. It was open to anyone, but we made a few targeted invitations to people who hold important pieces of that puzzle. What follows is a summary of what I learned in that meeting. It is only my personal perspective. I make no claim to speak for anyone else. I offer it in a spirit of openness, and in the hope to contribute to a broad, diverse, honest conversation. Taking part in such conversations is, I find, the main way we humans navigate problems as complex as this one.

About the listening event, and Edgeryders’s role in it

The listening event took place on April 9th, at 17.00 CEST as a Zoom conference call. We made it public through a post on the edgeryders.eu online forum. People learned of it mostly through Twitter. I have taken the initiative to reach out to some people whose opinion I was keen to hear. We discussed for two hours, with 32 to 36 people logged in at any given time. About 18 of them spoke at least once – I counted 11 male-sounding voices and 7 female-sounding ones. Their backgrounds and expertise was in:

-

The legal community.

-

The medical/public health community.

-

Digital tech. This was the largest group. People declared specializations in the fields of: information security; privacy; digital identity; artificial intelligence; big data analysis.

-

Privacy and human rights online.

-

Public policy and democratic participation therein.

-

Media.

My colleagues at Edgeryders and I participated as concerned citizens, like everyone else. But we were also working, because we we are part of a project called NGI Forward. Its role is to advise the European Commission on how to ensure that the future Internet upholds our common values of human rights and rule of law.

We adopted Chatham House rules. So, this post reports what people said, but not their names. The call was not recorded; I saved its chat to help me write this writeup, but then deleted the file. The information sheet contains full disclosure about our treatment of information from the event.

I take full responsibility for any incorrect reporting, and welcome any integration, correction or additional point of view. Please respond to this post, and let’s improve each other’s understanding.

Result 1: there is cause to worry, but also leverage for defense

There are several good reasons to be on our guard.

-

Policy makers tend to overestimate the effectiveness of technology-based surveillance vis-a-vis the pandemic. People spoke of pervasive solutionism (in the sense of Evgeny Mozorov – “a little magic dust can fix any problem”).

-

Digital surveillance companies are treating COVID-19 as a business opportunity. Some of these have dubious track records on the respect of human rights online. In the words of one participant:

In the last week, it’s been reported that around a dozen governments are using Palantir software and that the company is in talks with several more. They include agencies in Austria, Canada, Greece and Spain, the US, and the UK.

-

The public is scared, so willing to accept almost anything.

Example: in Italy, drones are being used to check distancing in public spaces. There are talks of equipping them with facial recognition algos. Is this necessary? Why? Is it going to become a permanent feature in our cities?

Another example: car manufacturer Ferrari has a plan called “back on track”. It involves re-opening the factory with a scheme that includes mandatory blood testing and a contact tracing app. Is this the kind of decision that your employer should make for you? What happens if you test positive?

There are two lines of defense against abuse of surveillance tech:

-

Data protection laws, starting with the GDPR. They all state that any data retention should be “necessary and proportionate” to the need it tries to solve. This is a weak defense, because all such laws provide exceptions for public safety. Also, governments and corporates have a history of ignoring “necessary and proportionate”.

-

If this fails, civil society can invoke the European Convention on Human Rights. This has its own court, which is not part of the EU, and so it is at arm’s length from the EU political space.

Result 2. Contact tracing apps are ineffective against COVID-19, but may help in the next pandemic

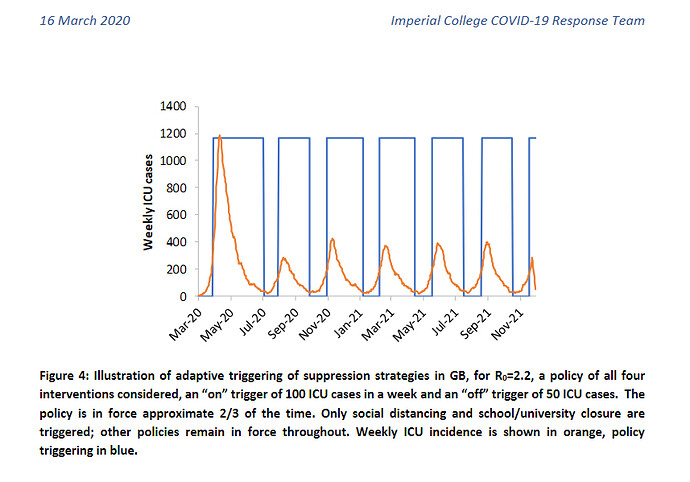

Everyone in the call, without exception, agreed that contact tracing apps won’t help against COVID-19. The rationale for building one such app, people explained, is to quickly quarantine everyone who got exposed to the first few cases. Once the virus spreads, confinement, as we have now, is a more appropriate measure. It is difficult to think that even the best app would prevent more contacts than people staying at home.

On top of this, these apps are easy to get wrong. Among failure modes, people cited:

-

Data governance issues: possible breaches, difficulty to anonymize the data, and so on. More on this below.

-

Lock-in effects: for these app to work, they need 50-60% of the population to take them on. It’s a “winner-take-it-all” service. There is potential for companies to lock authorities into long term contracts, invoke all kinds of confidentiality to protect their business models, and so on. This situation could prevent better solutions from emerging.

-

Loss of confidence: if the authorities roll out an app, and it does not deliver, the public may lose confidence in any app. This could happen as new cases rise again after lockdown is loosened, as is happening currently across Asia. This might burn an opportunity to help contain the next pandemic at an early stage.

So, why is everyone (including several people in our call!) building contact tracing apps? Because there is a political demand for it. It is linked to the end of the lockdown. Leaders are seen as doing nothing, while leaving people behind locked doors. They are eager to provide solutions. This, however, is very tricky to do. Evidence from Singapore shows that contact tracing is not working well to prevent new outbreaks. But what are the alternatives? Political leaders are reluctant to tell people “the danger is over, go back to your lives”. This is sure to backfire in the political arena if the epidemics enters a second wave.

This is where solutionism kicks in: building an app can be presented as “doing something about it”. On top of that, building apps is much faster, cheaper and easier, than, say, retooling the health care system. So, it’s a political win, though not an epidemiological one.

Several people pointed out that it is not a bad idea to build a contact tracing app. But it is a bad idea to rush it, because

- To be effective, tracing needs near-universal availability of testing, which is currently not there. Without this, contact tracing need to rely on self-reporting.

- To be effective, they also need a large, probably unrealistic, uptake (50-60%, where Singapore managed 12%).

- We will not need one until the next pandemic. Rushing development might lead to the deployment of evil, ineffective or broken solutions. One participant had this to offer:

I am currently involved with a group building a contact tracing app. But I am uneasy, actually thank you for giving voice to my anxieties. I do not see my colleagues discussing the use cases for this tech. I do not see them asking themselves if their solution is going to be effective. I do not see them discussing failure modes of the technologies. Almost everybody is hiding their head in the sand about the consequences of these solutions, intended or not.

So, the consensus in the group seemed to be for channeling tech repos

To keep it simple, most “obvious” solutions in an emergency turn out to be counter productive. […] You need to do your emergency homework in advance, and trust the experts. So for my contribution, I would argue you send every “develop an emergency app”/“do-something-itis” developer to work on future pandemic solutions, rather than give them reign in a crisis.

Result 3. Immunity passports are an unworkable idea

Another idea that is making the rounds is that of immunity passports. The group agreed that they can turn into a civil rights nightmare, As one participant said:

They are going to be basically “passport to civil liberties”. There are going to be a lot of perverse incentives around them.

One perverse incentive that came up:

Would that not create a huge incentive for people to go out and get infected, so they can get natural immunity? So nobody would want to do distancing, and we do not flatten the curve.

Over and above such concerns, it seems unlikely that immunity certificates would be effective. Issuing certificates means that having capacity to do massive-scale testing. We do not have that. If that capacity was there, we would be much better off in fighting COVID-19 with traditional anti-epidemic protocols, and not need immunity certificates. The medical professionals in the call also reminded us that we do not know how immunity works with SARS-CoV-2. How long does it last? Does it prevent reinfection, or only make it weaker? So, it’s not even clear what you would be certifying.

Result 4. Locational data are impossible to anonymize, and of limited utility. Capacity for data governance is bad

Participants agreed that it is not realistic to promise anonymization of locational data. A famous 2013 study shows that human mobility traces are highly unique. Four datapoints were enough to de-anonymize 95% of individuals in a large cellphone operator dataset. As one person put it:

I never trust a policy maker when they say “this data is going to be anonymized”. They do not understand what anonymisation means. And any solution will increase the amount of data in play.

As explained above, people were also sceptical on the usefulness of locational data in fighting the pandemic.

I do not think that you get any useful information from these apps. They will show that people get infected in places, like supermarkets or hospital, where people HAVE to come into contact with each other.

One participant offered these apps could help in assessing the efficacy of containment measures. That does not require granular data, but only pre-aggregated statistics. A recent paper on Science argues that it is possible to do this securely. The EFF has just released a policy proposal on this solution.

This was the one part of the conversation where I felt I could add my bit. After ten years of open data activism, I am pessimistic on the ability of EU governments and companies to do advanced, ethical governance of large datasets. The daily data on confirmed cases, hospitalizations and deaths are a mess. No standardization, no metadata, collection criteria that keep changing. Belgium, for example, on some days (but not every day!) reports on the same day the sum of two dishomogenous quantities:

-

number of people who died in hospital on that day, confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2, plus

-

number of people who died in the “last few days” in retirement homes, not tested (example).

Other example: the former head of Italy’s pension administration authority deplored the lack of open data on unemployment benefit claims. Scholars and policy makers themselves are flying blind, with no reliable data. How can we trust people who cannot maintain a Google spreadsheet to steward a massive trove of sensitive locational data?

A silver lining in all this is that contact tracing apps were battle-tested ten years ago. This means we have open datasets which can be used to model the impact of public health measures (example). If the goal is modelling, there is no need for more surveillance.

Result 5. Where to look for (pieces of) the solution

People offered several suggestions for where we could look for solutions, or at least improvements.

-

Medical and public health practitioners insisted on good execution over innovation. The WHO protocols, although devised for flu-type viruses, are well suited to coronaviruses as well. But their deployment was late and sloppy. Even at the time of writing, most EU countries cannot test at scale; they cannot provide adequate equipment. The medical community sees this emphasis on tech as misdirection. Part of any solution is to do public health well, without cutting corners. One participant from Italy remarked:

For example, we closed schools and universities, but did not inform students that they should not be hanging out with their friends. We did not tell students from different cities and regions to go back home. The rules are simple: if you are ill, tell your friends, and tell them to get tested. But in Italy it is hard to get tested, so the whole protocol fails. Contact tracing is the last thing we need. It is useless from a public health efficacy point of view, and not proportionate.

-

Other participants highlighted the positive of labor-intensive “boots on the ground”. A participant from the UK remarked:

I am worried that people fall off the cracks, because they are not on government databases and we do not see them. Maybe they are disabled, but have a job. They never touch the state, and fund their own care. I am worried about people with learning disabilities, for example. If you are not on social media, you have not seen the messages of your local authority, telling you where to get help.

-

Several people remarked that the tech community can have the greatest impact by playing a support role. They identified three areas to do this in. One is supporting what doctors are already doing, for example remote diagnosis or e-mail prescriptions. Another is supporting community organizers – another example of “boots on the ground”. The third one is the people manning the supply chain.

-

The tech community might find an important role to play in protecting the most vulnerable individuals from the worst consequences of the pandemic, and of the measures adopted to fight it. This was not mentioned in the call, but rather proposed in the ensuing online discussion.

-

There was agreement that it might helpful to lift IPR restrictions. We found one nice example in Italy, where a SME 3D-printed respirator valves that could not be obtained on the market fast enough to save lives.

We contacted the producer, a multinational, and asked them for the CAD file. They expressed reluctance and would not reach a decision. There are protocols, safety concerns. These are doubtlessly important. But there were people in need of saving, so we went ahead and reverse engineered it. […] We have not been sued so far.

-

Several people suggested that studying history (of epidemics, of technologies, of health and technology policies) could be useful. Solutionism has been with us for a long time (at least since the 1950s, according to a participant). Studying its successes (not many) and failure modes (many more) might help us not make the same mistake twice.

-

And finally, people called for more patient, open deliberation.

The dialog between the technologically possible and the politically acceptable needs to be had. Immediately it will be done by the elected politicians, that is what they are there for. Then, we should be moving to broader participation. We should be building technology for participation, as much as we should be building technology for tracing.

Amen to that. ![]()